Pharmacy and medical delivery drivers handle controlled substances, protected health information, and vulnerable patient populations—creating unique compliance obligations that extend far beyond standard employment screening. This guide examines the intersecting federal and state requirements governing pharmaceutical delivery personnel, from state pharmacy board mandates to HIPAA security rules, while addressing the criminal history factors that create unacceptable risk in roles involving Schedule II narcotics and patient access.

Key Takeaways

- Pharmacy delivery drivers require enhanced background screening due to access to controlled substances, protected health information, and vulnerable patients in residential settings, creating liability exposure that standard employment checks do not address.

- State pharmacy boards impose specific criminal history disqualifications for individuals with access to prescription medications, with many states mandating fingerprint-based FBI checks and automatic bars for drug-related convictions within defined lookback periods.

- HIPAA Security Rule obligations apply to delivery personnel who handle prescription information or enter patient homes, requiring workforce clearance procedures and ongoing supervision to prevent unauthorized disclosure of protected health information.

- Controlled substance diversion by delivery staff has resulted in criminal prosecutions, DEA sanctions against pharmacies, and civil liability exceeding $2 million in documented cases where inadequate screening allowed employees with disqualifying histories to access Schedule II medications.

- State-specific variations create complex compliance requirements across jurisdictions, with California, New York, Texas, and Florida imposing distinct screening mandates, disqualification standards, and documentation requirements that differ substantially from federal baseline rules.

- Motor vehicle record monitoring is a continuous compliance obligation for pharmacy delivery operations, as driving infractions, license suspensions, or DUI convictions create immediate liability risks that initial screenings cannot detect.

- Patient safety incidents attributable to inadequate screening include theft of opioid medications, identity theft using patient information accessed during deliveries, and physical harm to elderly patients by employees with violent criminal histories.

- Documentation and retention of screening decisions provides essential legal protection in negligent hiring claims, requiring written policies that demonstrate individualized assessment, consideration of offense relevance, and adherence to FCRA adverse action procedures when criminal history leads to disqualification.

Understanding Regulatory Authority Over Pharmacy Delivery Personnel

Pharmacy delivery operations exist within overlapping regulatory frameworks that create layered compliance obligations. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration exercises authority over any individual with access to controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act. State pharmacy boards govern who may handle prescription medications within their jurisdictions. Meanwhile, the Department of Health and Human Services enforces HIPAA requirements that extend to delivery staff who encounter protected health information during their duties.

Federal Controlled Substances Access Requirements

The DEA does not require universal background checks for all pharmacy employees. However, the agency mandates that registrants—including pharmacies dispensing controlled substances—maintain effective controls against diversion. DEA regulations at 21 CFR § 1301.90 require registrants to screen employees who will have access to controlled substances, though the specific screening method remains at the registrant's discretion.

This creates baseline federal expectations that pharmacy operators will implement reasonable measures to prevent individuals with drug trafficking histories or substance abuse patterns from accessing Schedule II through V medications. Pharmacies that experience controlled substance theft or diversion face DEA investigations that scrutinize employee screening practices. Administrative actions and civil penalties have been imposed on pharmacies that employed delivery drivers with recent drug-related convictions without documented justification for the hiring decision.

State Pharmacy Board Screening Mandates

State pharmacy boards impose more specific requirements that vary significantly across jurisdictions. Many states require criminal background checks for any individual employed by a pharmacy who will have access to prescription medications or patient information. These mandates typically specify fingerprint-based FBI checks rather than name-based searches, ensuring detection of out-of-state criminal history that might escape commercial database screening.

States including California, New York, and Texas require submission of fingerprints to state agencies that coordinate with the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services division. Automatic disqualification periods apply for specific offense categories, most commonly drug manufacturing or trafficking convictions, theft crimes, and violent felonies. The lookback period varies by state, with some imposing permanent bars for certain convictions while others allow consideration after five to ten years. Ongoing reporting obligations require pharmacy operators to notify the state board when an employee is arrested or convicted after initial hire.

HIPAA Workforce Security Requirements

The HIPAA Security Rule at 45 CFR § 164.308(a)(3) requires covered entities to implement policies and procedures that ensure workforce members have appropriate access to electronic protected health information. These policies must also prevent unauthorized access. While HIPAA does not mandate specific background check procedures, the security rule's workforce clearance provision creates compliance expectations that delivery personnel who view prescription labels, patient names, addresses, or medication information undergo screening appropriate to their access level.

Pharmacy delivery drivers routinely encounter protected health information in the course of their duties. They see patient names, addresses, prescribed medications, and dosage instructions. In many cases, they enter patient homes and interact directly with individuals receiving treatment for sensitive conditions. Consequently, the HIPAA Security Rule's risk analysis and workforce security requirements compel pharmacy operators to assess whether criminal history factors create unacceptable risk of unauthorized PHI disclosure, particularly theft of patient information for identity fraud purposes.

Criminal History Factors That Create Unacceptable Risk

Not all criminal history creates equal risk in pharmaceutical delivery roles. Compliance officers must understand which offense categories correlate with specific risk scenarios unique to pharmacy operations. These scenarios include controlled substance access, vulnerable patient contact, and confidential information handling.

Drug-Related Convictions and Diversion Risk

Convictions for drug possession, distribution, or manufacturing represent the highest-risk category for pharmacy delivery positions. Documented diversion cases frequently involve employees with substance use disorders or prior involvement in illegal drug markets. Pharmacies face heightened DEA scrutiny when diversion incidents involve staff members with drug-related criminal histories that were known or discoverable at hire.

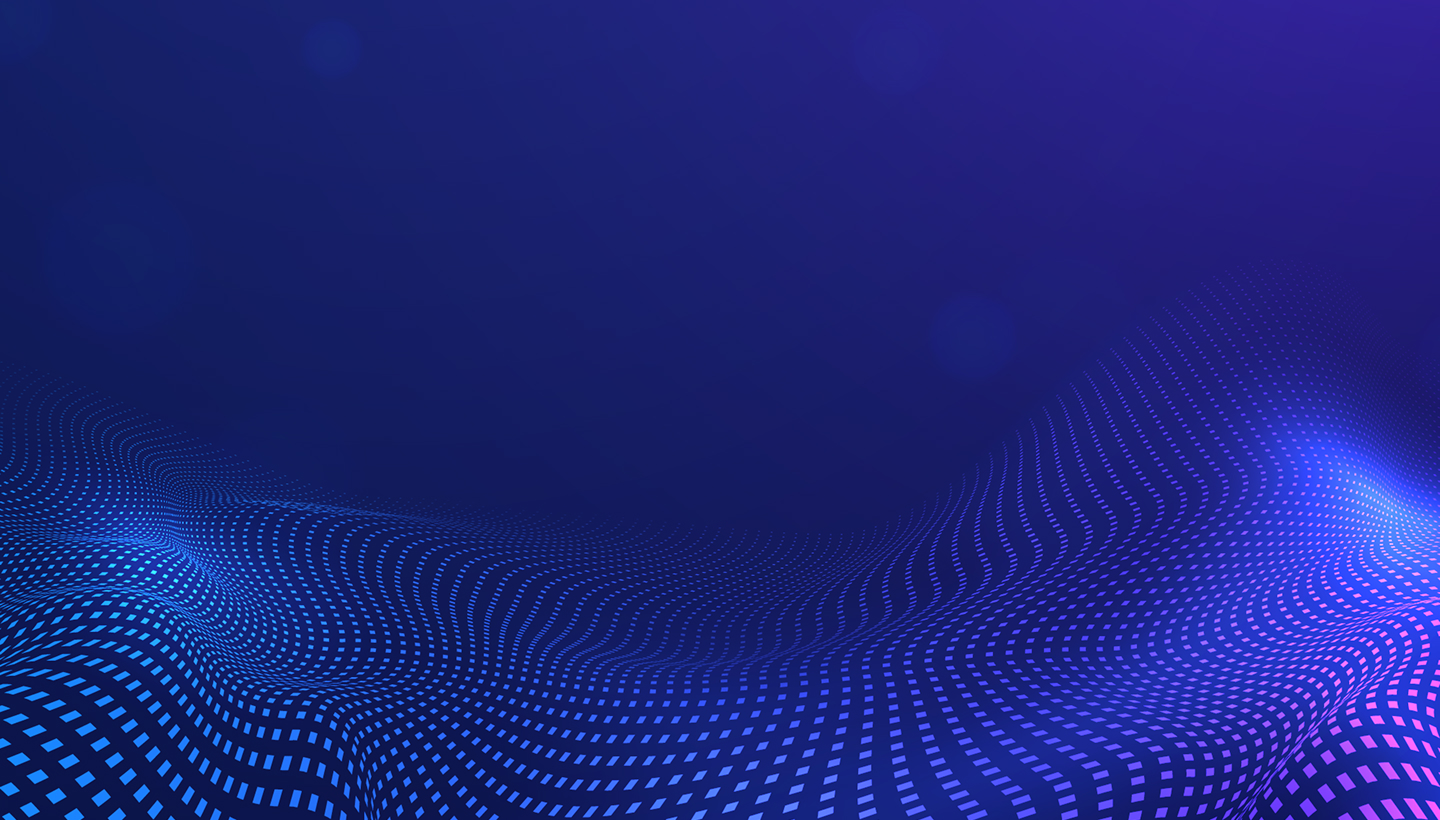

The critical analysis focuses on three key factors:

- Recency: A single marijuana possession charge from a decade ago presents materially different risk than methamphetamine trafficking convictions within the past three years.

- Severity: Drug trafficking or manufacturing convictions indicate substantially higher diversion risk than simple possession offenses.

- Pattern behavior: Multiple drug-related offenses suggest ongoing substance involvement that increases diversion probability regardless of time elapsed.

State pharmacy boards commonly impose absolute bars for drug trafficking convictions within specified lookback periods, typically five to ten years. Even when state law permits discretionary hiring, the liability risk and DEA scrutiny make such decisions exceptionally high-risk for pharmacy operators.

Theft Offenses and Medication Security

Theft convictions directly correlate with medication diversion and patient information misuse scenarios. Particularly concerning are offenses involving workplace theft, prescription fraud, or identity theft. Delivery drivers have unsupervised access to high-value controlled substances during transport and frequently work without direct oversight in patient homes.

Documented incidents include delivery personnel who stole patient credit card information observed during home deliveries. Other cases involve employees who diverted opioid prescriptions during transport. Additionally, drivers have committed burglaries at patient residences after identifying vulnerable elderly individuals during routine deliveries. Theft offense analysis considers both the theft target and the method employed.

Violent Crimes and Patient Safety

Delivery drivers enter patient homes, often interacting with elderly, disabled, or medically vulnerable individuals in isolated settings. Violent crime convictions create unacceptable patient safety risks in these circumstances. Offenses such as assault, domestic violence, robbery, and sexual offenses warrant particular scrutiny.

Negligent hiring liability has been established in cases where delivery personnel with violent criminal histories committed assaults or thefts in patient homes. Pharmacy operators owe a duty of reasonable care in screening employees who will have unsupervised access to vulnerable individuals. Failure to discover readily available violent crime history through background checks creates significant liability exposure. The individualized assessment required under EEOC guidance becomes particularly challenging with violent offense histories, though the direct nexus between violent criminal history and patient safety risk in home delivery settings makes disqualification defensible in most scenarios.

State-Specific Compliance Requirements

Pharmacy delivery screening compliance requires navigation of jurisdiction-specific mandates that vary substantially in scope, method, and disqualification standards. Operations serving multiple states must implement screening protocols that satisfy the most stringent applicable requirement. Understanding these variations is essential for maintaining compliance across different markets.

California Pharmacy Law Requirements

California Business and Professions Code § 4160 requires criminal background checks for pharmacy licensure applicants. The California State Board of Pharmacy has extended screening expectations to employees with access to controlled substances through policy guidance. The Board requires LiveScan fingerprint submission for pharmacy technicians and recommends similar screening for delivery personnel who transport or have custody of prescription medications.

California's "ban-the-box" law (Government Code § 12952) prohibits criminal history inquiries before conditional job offers but provides exceptions for positions where background checks are required by law. Pharmacy delivery roles fall within this exception when screening is mandated by federal DEA regulations or state Board of Pharmacy requirements. Criminal history disqualification factors under California law include convictions for controlled substance offenses, with rehabilitation evidence receiving significant weight after seven years.

New York State Pharmacy Board Standards

New York Education Law § 6810 and Part 63 of the Commissioner's Regulations require criminal background checks for pharmacy licensure. Fingerprint-based FBI checks are mandatory for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. While delivery drivers who do not prepare or dispense medications may not require formal registration, the New York State Board of Pharmacy has issued guidance stating that employees with access to controlled substances should undergo equivalent screening.

New York's Article 23-A provides strong fair hiring protections. The law requires consideration of eight statutory factors before denying employment based on criminal history. These factors include the relationship between the offense and employment duties, time elapsed, and rehabilitation evidence. However, the direct nexus between drug trafficking convictions and pharmaceutical delivery roles provides clear grounds for disqualification under the Article 23-A analysis.

Texas Health and Safety Code Mandates

Texas Health and Safety Code § 481.066 requires criminal history checks for individuals with access to controlled substances in healthcare settings. The Texas State Board of Pharmacy interprets this provision to include pharmacy delivery personnel who transport Schedule II through V medications. Consequently, the Board requires name-based criminal history checks at minimum, with fingerprint-based FBI checks recommended for roles involving Schedule II narcotics.

| Offense Category | Disqualification Period | Special Conditions |

| Felony controlled substance convictions | 10 years | Automatic bar from access |

| Misdemeanor drug offenses | 5 years | May require individualized review |

| Drug trafficking to minors | Permanent | No exceptions permitted |

| Theft or fraud felonies | 7 years | Case-by-case assessment allowed |

These bright-line rules reduce the individualized assessment complexity but may conflict with EEOC guidance in specific scenarios.

Florida Administrative Code Provisions

Florida Administrative Code Rule 64B16-26.101 establishes background screening requirements for pharmacy technicians and supportive personnel. While the rule does not explicitly mandate screening for delivery drivers, the Florida Board of Pharmacy has issued advisory opinions stating that employees who transport controlled substances should undergo Level 2 background screening. This screening includes fingerprint-based FBI checks and Florida Department of Law Enforcement records review.

Florida's screening statute at Chapter 435, Florida Statutes, lists disqualifying offenses for positions involving access to controlled substances or vulnerable populations. Permanent disqualification applies to convictions for drug trafficking, sexual offenses, and violent felonies. Time-limited bars of three to fifteen years apply to theft, fraud, and simple drug possession convictions depending on severity.

HIPAA Compliance in Delivery Operations

Protected health information security extends beyond pharmacy walls into delivery vehicles and patient homes. HIPAA compliance for pharmacy delivery operations requires specific workforce policies that address the unique privacy and security risks. These risks emerge when prescription information leaves the controlled pharmacy environment.

Protected Health Information Exposure During Deliveries

Delivery drivers necessarily access protected health information to perform their job duties. Prescription labels contain patient names, addresses, prescribing physician information, diagnosis codes, medication names, dosages, and refill instructions. All of these elements constitute PHI under HIPAA definitions at 45 CFR § 160.103.

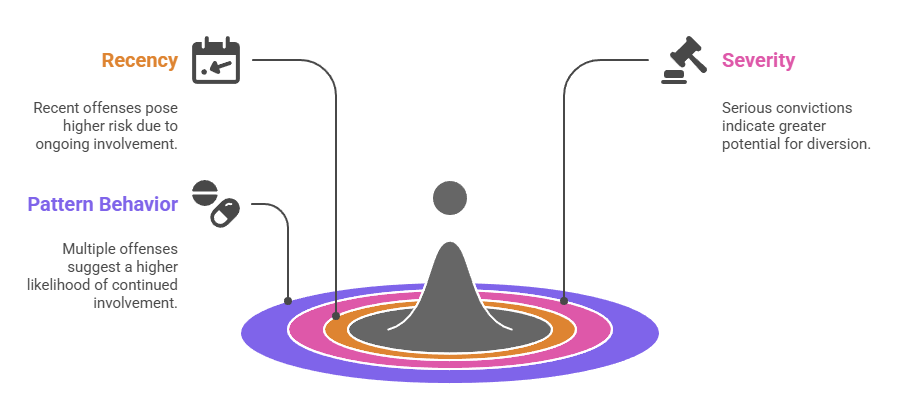

The delivery process creates multiple exposure points:

- In-transit visibility: Prescription packages may be visible to other individuals if not properly secured in delivery vehicles.

- Home environment observation: Drivers may observe additional health information including medical equipment, mobility aids, or other medications visible in patient residences.

- Patient interactions: Conversations with patients or family members may reveal diagnosis information, treatment adherence issues, or other sensitive health details.

- Delivery verification procedures: Confirmation protocols may inadvertently expose medication details to household members or neighbors.

These exposure scenarios require specific security measures to minimize unauthorized access while maintaining delivery safety and accuracy.

Workforce Clearance Procedures Under HIPAA Security Rule

The HIPAA Security Rule requires covered entities to implement procedures for determining that workforce member access to electronic PHI is appropriate. While pharmacy delivery drivers may not access electronic systems directly, they handle physical manifestations of ePHI in the form of printed prescription labels generated from pharmacy management systems. Compliance with the workforce clearance standard requires documented screening procedures that assess fitness for access to protected health information.

Criminal history factors particularly relevant to HIPAA compliance include identity theft or fraud convictions, which indicate risk of misusing patient information for financial gain. Delivery drivers have repeated access to names, addresses, dates of birth, and medication information that could enable identity fraud or insurance scams. Computer crimes or unauthorized access convictions suggest elevated risk of improper PHI access if drivers have any access to pharmacy systems or portable devices containing patient information. Prior healthcare fraud or abuse convictions create presumptive disqualification under most HIPAA compliance programs, as these offenses directly demonstrate willingness to misuse healthcare information or resources.

Minimum Necessary Access Limitations

HIPAA's minimum necessary standard at 45 CFR § 164.502(b) requires covered entities to limit PHI access to the minimum necessary to accomplish the intended purpose. For delivery operations, this translates to protocols that minimize the patient information visible to drivers. At the same time, these protocols must maintain medication safety and proper delivery verification.

| Security Measure | Implementation Method | Compliance Benefit |

| Concealed label packaging | Outer wrapper covers detailed prescription information | Reduces in-transit PHI exposure |

| Secure transport containers | Locked bags or cases prevent unauthorized viewing | Limits access during vehicle operation |

| Limited delivery confirmation | Verification by patient name only without medication discussion | Minimizes disclosure in multi-resident settings |

| Electronic signature capture | Device-based confirmation without verbal information exchange | Reduces conversation-based PHI exposure |

These strategies balance operational efficiency with privacy protection requirements.

Motor Vehicle Record Monitoring Requirements

Driving history screening for pharmacy delivery personnel serves dual compliance purposes. First, it mitigates liability for vehicle operation. Second, it assesses judgment factors relevant to medication custody. Motor vehicle record monitoring must be continuous rather than one-time, as license status and driving infractions change throughout employment.

Initial Driving History Evaluation

Pre-employment motor vehicle record checks identify disqualifying factors that create unacceptable liability risk for pharmacy delivery operations:

- License suspension or revocation: Rendering the applicant legally unable to operate a vehicle creates immediate disqualification. Suspended licenses often result from DUI convictions, excessive point accumulation, or failure to maintain required insurance—all factors suggesting poor judgment or legal non-compliance.

- DUI or impaired driving convictions: Within three to five years indicate substance use issues that create elevated risk in roles involving controlled substance access. Beyond the driving safety implications, recent DUI history correlates with substance use disorders that increase medication diversion probability.

- Reckless driving or excessive moving violations: Suggest pattern behavior indicating poor judgment, inability to follow safety rules, or disregard for legal requirements—characteristics that create risk in unsupervised delivery roles involving valuable medications.

Each of these factors requires documented evaluation and decision-making to support defensible hiring determinations.

Ongoing MVR Monitoring Protocols

License status and driving history change continuously throughout employment. A driver hired with a clean record may subsequently accumulate violations, lose driving privileges, or receive DUI convictions that create new disqualifying factors. Pharmacy operators face negligent retention liability when employees with suspended licenses or recent serious violations continue in delivery roles.

Effective ongoing monitoring requires either periodic MVR checks at defined intervals (typically annually) or enrollment in continuous monitoring services that provide alerts when license status changes or new violations occur. The monitoring frequency should reflect the risk level associated with the delivery operation. Operations transporting Schedule II narcotics warrant more frequent monitoring than those delivering only non-controlled medications. Documentation of monitoring frequency decisions demonstrates risk-based decision-making in potential liability scenarios.

FCRA Compliance in Adverse Action Procedures

When criminal history or driving record information obtained through consumer reporting agencies leads to disqualification decisions, federal Fair Credit Reporting Act requirements mandate specific procedural steps. These steps protect applicant rights and limit employer liability. Strict adherence to FCRA procedures is essential to avoid statutory damages and penalties.

Pre-Adverse Action Notice Requirements

Before taking adverse action based on information in a consumer report, employers must provide the individual with a pre-adverse action disclosure. This disclosure must include a copy of the consumer report and the FTC's Summary of Rights document as required by 15 U.S.C. § 1681b(b)(3). The notice must occur before the final decision is made, providing the individual opportunity to dispute inaccurate information or provide context for accurate but potentially misleading records.

The pre-adverse action waiting period should provide reasonable time for response—typically five to seven business days—before proceeding to final adverse action. During this period, the pharmacy must consider any information the applicant provides that bears on the accuracy or interpretation of the background check findings. Failure to allow adequate response time or consider applicant explanations creates FCRA liability exposure.

Individualized Assessment Documentation

EEOC enforcement guidance requires individualized assessment of criminal history rather than blanket disqualification rules. This requirement applies particularly when the policy would create disparate impact on protected groups. The assessment must consider the nature and gravity of the offense, time elapsed since the conviction, and the nature of the job sought.

For pharmacy delivery positions, the individualized assessment should document the specific nexus between the criminal history and job duties:

- Drug trafficking convictions: Have a direct and obvious relationship to roles involving controlled substance access.

- Theft convictions: Relate clearly to unsupervised handling of valuable medications.

- Violent crime history: Connects directly to patient safety risks in home delivery settings.

Documentation should include written analysis of these factors rather than conclusory statements. This creates a record that demonstrates reasoned decision-making rather than arbitrary disqualification.

Final Adverse Action Notice

When the decision is made to deny employment or terminate based on background check information, the employer must provide a final adverse action notice. This notice must contain the name, address, and phone number of the consumer reporting agency that provided the report. Additionally, it must include a statement that the CRA did not make the adverse decision, notice of the individual's right to dispute the report's accuracy, and notice of the right to request an additional free copy of the report within 60 days.

The final notice requirement exists separately from any state-specific adverse action procedures. Employers must satisfy this requirement even when state law imposes additional notification obligations.

Liability Scenarios From Inadequate Screening

Documented legal cases and regulatory actions demonstrate the tangible consequences of insufficient background screening in pharmacy delivery operations. These precedents establish the standard of care expected from pharmacy operators. They also illustrate the damages that may result from screening failures.

Controlled Substance Diversion by Delivery Personnel

A regional pharmacy chain settled a DEA civil penalty action for $850,000 after delivery drivers with prior drug trafficking convictions diverted more than 10,000 oxycodone tablets over an 18-month period. The DEA investigation determined that the pharmacy had not conducted criminal background checks on delivery personnel despite policy statements requiring such screening. The settlement included enhanced screening protocols and ongoing DEA monitoring of the pharmacy's compliance measures.

In a separate case, a specialty pharmacy faced criminal charges for distribution of controlled substances after an employee with three prior drug-related convictions systematically stole Schedule II medications during deliveries. The employee sold the stolen medications to street dealers. Prosecutors argued that the pharmacy's failure to screen the employee constituted willful blindness to the diversion risk, supporting criminal rather than merely civil liability.

Patient Harm From Employees With Violent Histories

A pharmacy in the Southeastern United States faced a $2.3 million negligent hiring judgment after a delivery driver with prior assault and burglary convictions assaulted and robbed an elderly patient during a prescription delivery. Discovery revealed that the pharmacy had not conducted criminal background checks on delivery personnel. Instead, the pharmacy relied on self-reported criminal history on employment applications.

The employee had falsely stated he had no criminal record. The pharmacy made no effort to verify the information. The jury found that the pharmacy owed a duty of reasonable care to screen employees who would enter patient homes. Furthermore, standard practice in the pharmacy industry included criminal background checks for delivery personnel. The pharmacy's failure to conduct such screening approximately caused the patient's injuries.

HIPAA Violations and Identity Theft

A pharmacy delivery driver with prior identity theft convictions used patient information obtained during deliveries to file fraudulent tax returns and credit applications. The scheme affected more than 40 patients and continued for two years before discovery. The pharmacy faced the HHS Office for Civil Rights investigation and ultimately agreed to a $275,000 HIPAA settlement for failure to implement appropriate workforce screening and supervision.

The OCR determination noted that the employee's criminal history was readily discoverable through routine background screening. Moreover, the prior identity theft convictions created obvious and foreseeable risk of PHI misuse in a role involving patient name, address, and date of birth access. This case established that HIPAA's workforce security provisions require screening that addresses criminal history relevant to PHI protection.

Implementing Compliant Screening Programs

Effective pharmacy delivery background screening requires written policies that specify screening scope, evaluation criteria, and decision procedures. These policies must satisfy federal FCRA requirements, state-specific mandates, and EEOC fair hiring standards. Clear documentation protects against both regulatory penalties and civil liability.

Screening Scope and Timing

Comprehensive screening for pharmacy delivery positions should include criminal history searches at county, state, and federal levels. Additional components include sex offender registry checks, motor vehicle record review, and verification of driving license validity. For operations in states requiring fingerprint-based FBI checks, the screening must include submission to the appropriate state agency for processing.

Screening should occur after a conditional offer of employment has been extended, satisfying ban-the-box requirements in jurisdictions imposing such restrictions. The conditional offer should explicitly state that employment is contingent on satisfactory completion of required background checks. Additionally, the offer must clearly define what constitutes "satisfactory" results to avoid ambiguity that could create discrimination claims.

Criminal History Evaluation Criteria

Written policies should specify which criminal conviction categories create presumptive disqualification based on the direct relationship to job duties and patient safety risks:

| Offense Category | Standard Lookback Period | Risk Nexus |

| Drug trafficking or manufacturing | 10 years | Direct controlled substance access risk |

| Drug possession | 5 years | Substance abuse correlation with diversion |

| Theft, fraud, or embezzlement | 7 years | Unsupervised medication custody |

| Violent crimes (assault, robbery, sexual offenses) | 10 years | Patient safety in home settings |

| Sex offender registration | Indefinite | Vulnerable patient contact |

The policy should clarify that these categories create presumptive rather than absolute disqualification. This allows for individualized consideration of mitigating factors including evidence of rehabilitation, age at offense, single versus pattern offenses, and offense circumstances.

Ongoing Screening and Re-Evaluation

Employment screening for pharmacy delivery personnel should not be one-time. Policies should require ongoing motor vehicle record monitoring at least annually. Additionally, they should specify procedures for employee notification when arrests or convictions occur after hire.

Many state pharmacy board regulations require employees to report arrests or criminal charges. Pharmacy operators are then obligated to conduct fitness reassessments based on the new information. Failure to implement ongoing monitoring creates negligent retention exposure when post-hire criminal conduct or license suspensions go undetected.

Conclusion

Pharmacy delivery driver screening requires heightened diligence that reflects unique risks created by controlled substance access, patient home entry, and protected health information handling. Compliance demands understanding of overlapping DEA expectations, state pharmacy board mandates, and HIPAA workforce security obligations that extend beyond standard employment screening. Documented liability cases demonstrate that inadequate screening creates foreseeable risk of medication diversion, patient harm, and privacy violations that expose pharmacy operators to criminal penalties, civil damages, and regulatory sanctions exceeding $2 million in documented cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

What criminal convictions automatically disqualify pharmacy delivery driver applicants?

No federal law creates absolute automatic disqualification, but state pharmacy boards commonly impose bars for drug trafficking convictions within 5-10 years. EEOC guidance requires individualized assessment rather than blanket exclusions. However, drug-related convictions, theft offenses, and violent crimes have direct nexus to safety risks in pharmaceutical delivery roles, making case-by-case disqualification legally defensible when properly documented.

Are fingerprint-based FBI background checks required for pharmacy delivery drivers?

Requirements vary by state—California, New York, Texas, and Florida either require or strongly recommend fingerprint-based FBI checks for pharmacy employees with controlled substance access. Even when not legally mandated, FBI checks provide more comprehensive criminal history than commercial database searches. These checks are particularly valuable for detecting out-of-state convictions, making them advisable for roles involving Schedule II narcotics access regardless of state requirements.

How do HIPAA regulations apply to pharmacy delivery personnel who never access computer systems?

HIPAA Security Rule workforce clearance requirements apply to employees who access protected health information in any form, including printed prescription labels. Delivery drivers routinely view patient names, addresses, medications, and dosages—all constituting PHI under HIPAA definitions. Screening must assess criminal history factors indicating risk of unauthorized PHI disclosure, particularly identity theft, fraud, or prior healthcare abuse convictions.

What is the appropriate lookback period for criminal history in pharmacy delivery screening?

The EEOC discourages lookback periods exceeding seven years unless required by law, but state pharmacy boards may impose longer periods for specific offense categories. Drug trafficking convictions typically receive 10-year lookback periods, while violent felonies may be considered indefinitely when patient safety risk exists. The appropriate period depends on offense severity, relevance to job duties, and applicable state law rather than a single universal standard.

Can pharmacies refuse to hire applicants with DUI convictions for delivery positions?

Recent DUI convictions (within 3-5 years) provide legally defensible grounds for disqualification based on direct relationship to controlled substance access risk and vehicle operation safety. DUI convictions indicate impaired judgment relevant to medication custody responsibilities and create unacceptable liability risk for driving duties. Individualized assessment should consider conviction recency and whether it represents pattern behavior versus an isolated incident.

What adverse action procedures must be followed when criminal history leads to disqualification?

The Fair Credit Reporting Act requires pre-adverse action notice including a copy of the background check report and Summary of Rights. Applicants must receive reasonable time to respond (typically 5-7 days), followed by individualized assessment considering offense nature and relevance to job duties. Final adverse action notice must identify the screening company and explain dispute rights. State laws may impose additional notice requirements that must be satisfied separately from FCRA mandates.

How frequently should motor vehicle records be monitored for active delivery employees?

Continuous monitoring or annual MVR checks represent minimum best practice, with more frequent screening appropriate for operations involving Schedule II narcotics transport. License suspensions, DUI arrests, or serious moving violations create immediate disqualification factors for driving positions. Failure to detect such changes through ongoing monitoring creates negligent retention liability when incidents occur after license revocation or suspension.

Do ban-the-box laws prohibit criminal history screening for pharmacy delivery positions?

Most ban-the-box laws prohibit criminal history inquiries before conditional job offers but include exceptions for positions where screening is required by law. Pharmacy delivery roles often fall within these exceptions due to DEA regulations requiring diversion controls and state pharmacy board mandates. Even where exceptions do not apply, screening may proceed after conditional offers are extended, satisfying ban-the-box timing requirements.

Additional Resources

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration – Pharmacist's Manual

https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pharm2/pharm_manual.htm - U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – HIPAA Security Rule Guidance

https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/security/index.html - Federal Trade Commission – Fair Credit Reporting Act Consumer Rights

https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/fair-credit-reporting-act - U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission – Background Checks and Employment

https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/enforcement-guidance-consideration-arrest-and-conviction-records-employment - National Association of Boards of Pharmacy – Model State Pharmacy Act

https://nabp.pharmacy/programs/professional-affairs/model-pharmacy-act/

GCheck Editorial Team

Meet the GCheck Editorial Team, your trusted source for insightful and up-to-date information in the world of employment background checks. Committed to delivering the latest trends, best practices, and industry insights, our team is dedicated to keeping you informed.

With a passion for ensuring accuracy, compliance, and efficiency in background screening, we are your go-to experts in the field. Stay tuned for our comprehensive articles, guides, and analysis, designed to empower businesses and individuals with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions.

At GCheck, we're here to guide you through the complexities of background checks, every step of the way.