Continuous monitoring of senior care staff has evolved from an optional safeguard into a regulatory and operational necessity for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. As state licensing requirements tighten and family expectations rise, relying solely on pre-hire background checks leaves facilities exposed to liability, compliance deficiencies, and preventable incidents involving vulnerable adults.

Key Takeaways

- Continuous monitoring detects post-hire arrests, credential lapses, and exclusion list additions that standard background checks cannot capture.

- Federal and state requirements for ongoing screening vary widely, but the trend across jurisdictions is toward stricter and more frequent verification obligations.

- Senior living facilities face unique workforce challenges, including high turnover, reliance on agency staff, and multi-state credential requirements.

- Pre-hire screening alone is insufficient in environments where staff churn often exceeds 50% annually and per-diem workers rotate frequently.

- Elder abuse risk factors include financial exploitation, physical harm, and neglect, all of which can be mitigated through vigilant post-hire monitoring.

- Staffing agencies may not provide adequate screening coverage, leaving facilities legally responsible for gaps in oversight.

- Licensing surveys and accreditation reviews increasingly scrutinize documentation of ongoing staff monitoring programs.

- Implementation requires integration with HR systems, clear alert triage protocols, and scalable workflows suited to facility size and resources.

Defining Continuous Monitoring in the Senior Living Context

Continuous monitoring refers to the systematic, automated review of employee records after hire to detect criminal activity, credential status changes, or eligibility disqualifications that emerge during employment. Unlike periodic re-screening, which occurs at fixed intervals such as annually or biennially, continuous monitoring operates on an ongoing basis, often checking databases daily or weekly.

How Continuous Monitoring Differs from Related Practices

Pre-hire background checks provide a snapshot of an applicant's history at a single point in time. Once the candidate is hired, that snapshot becomes outdated. Continuous monitoring senior care staff extends the detection window throughout the employment relationship, capturing events that occur after the hire date.

Periodic re-screening, while more robust than one-time checks, still leaves gaps. An employee arrested in month three of a twelve-month re-screening cycle may interact with residents for nine additional months before the facility becomes aware of the issue. Continuous monitoring closes this window by providing near-real-time alerts when new criminal records, sanctions, or credential revocations appear.

Why Precision Matters for Senior Living Administrators

The senior living sector operates under a dense web of federal, state, and local regulations. Misunderstanding what continuous monitoring entails can lead to non-compliance, undetected risk, and false confidence. Facilities that believe they are conducting continuous monitoring but are actually performing annual re-checks may fail to meet evolving state requirements or miss critical incidents.

Continuous monitoring in senior living must account for databases specific to healthcare and vulnerable populations. These include state nurse aide registries, federal exclusion lists maintained by the Office of Inspector General, sex offender registries, and state abuse and neglect registries. Generic continuous monitoring services designed for non-healthcare industries may omit these sources, leaving gaps in coverage.

The Regulatory Landscape: Federal Requirements and State Variation

Understanding compliance obligations for senior living employee screening requires navigating a layered framework of federal mandates, state licensing statutes, and local ordinances. No single federal law dictates uniform continuous monitoring requirements for all senior living facilities, but several federal programs and regulations establish baseline expectations.

| Regulatory Level | Key Requirements | Monitoring Implications |

| Federal (CMS) | Staff cannot appear on exclusion lists; ongoing eligibility verification required | Practical need for regular OIG/SAM checks |

| State Licensing | Varies by state; may require annual checks, continuous monitoring, or quarterly verifications | Must align facility policy with most restrictive applicable standard |

| Local Ordinances | Some municipalities impose additional screening or reporting obligations | Requires jurisdiction-specific review |

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services sets conditions of participation for nursing homes that accept Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement. These conditions establish that facilities must not employ individuals listed on federal exclusion lists, including the OIG List of Excluded Individuals and Entities and the General Services Administration's System for Award Management exclusion records. While CMS does not prescribe specific verification frequencies, the obligation to maintain ongoing compliance creates an operational need for regular monitoring.

State-Level Variability

State requirements vary significantly. Some mandate annual criminal background checks for all staff with direct resident contact, others require continuous monitoring of specific databases, and still others impose quarterly or periodic verification obligations. Requirements also differ based on facility type, staff role, and whether the state participates in specific federal programs.

Lookback periods, the timeframe during which criminal history is considered, differ by state. Some jurisdictions impose lifetime disqualifications for specific offenses, while others limit consideration to convictions within defined periods such as seven or ten years. Additionally, some states prohibit consideration of arrest records without conviction, require individualized assessments before disqualification, or restrict inquiry into criminal history until later in the hiring process. Facilities must ensure their policies comply with applicable fair chance hiring laws and criminal history use restrictions.

Certain states have enacted laws requiring facilities to check databases specific to healthcare workers, such as nurse aide registries and medication aide registries. Failure to verify that a certified nursing assistant is in good standing with the state registry can result in surveyors citing deficiencies during licensing inspections.

Practical Implications for Administrators

Administrators must verify current requirements with state licensing agencies and legal counsel. Regulations evolve, and what was compliant last year may fall short of new standards. Facilities operating in multiple states must navigate these inconsistencies. While some organizations adopt the most restrictive substantive standard as a baseline, they must also ensure compliance with state-specific procedural requirements, disclosure obligations, and candidate rights that may not be satisfied by a single uniform policy. Facilities should document their interpretation of applicable laws and maintain records showing how screening policies align with regulatory obligations.

What Screening Checks Apply to Senior Living Staff Specifically

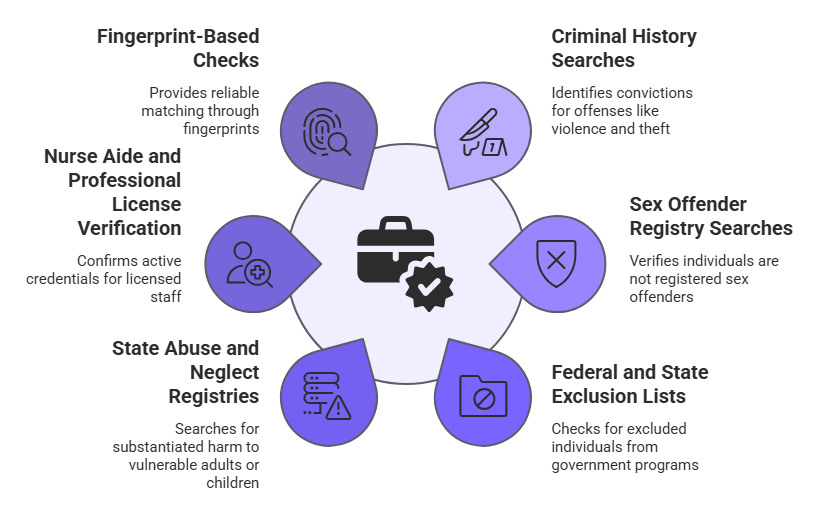

Senior living facilities must conduct a broader range of checks than many other industries due to the vulnerability of the population served and the regulatory requirements governing healthcare workers. The following checks are commonly required or strongly recommended:

- Criminal History Searches: Identify convictions and sometimes arrests for offenses that may preclude employment, typically including crimes involving violence, abuse, neglect, exploitation, theft, fraud, and controlled substances, though specific prohibitions and the scope of individualized assessment requirements vary by jurisdiction

- Sex Offender Registry Searches: Verify individuals are not registered sex offenders, which typically violates state licensing standards

- Federal and State Exclusion Lists: Check OIG LEIE and SAM exclusion records to prevent employment of excluded individuals

- State Abuse and Neglect Registries: Search registries of individuals substantiated for harm to vulnerable adults or children

- Nurse Aide and Professional License Verification: Confirm CNAs appear on state registries in good standing and that licensed staff hold active credentials

- Fingerprint-Based Checks: Required in some states for more reliable matching than name-based searches

Facilities should determine whether state law requires county-level, state-level, or multi-jurisdictional searches. National criminal databases compiled by private data vendors provide broad coverage but may lack completeness or currency. County-level searches, though slower, often provide more accurate and up-to-date records.

Federal and State Exclusion Lists

The Office of Inspector General maintains the List of Excluded Individuals and Entities, which identifies individuals and organizations barred from participating in federal healthcare programs due to fraud, abuse, or other misconduct. Employing an excluded individual can result in loss of Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, substantial fines, and criminal liability. The General Services Administration maintains the System for Award Management exclusion records, which include individuals and entities debarred from federal contracts and assistance programs.

Facilities must check these lists before hire and periodically thereafter. Many compliance officers check monthly, though continuous monitoring systems can automate this process.

The Operational Case: Why Pre-Hire Screening Alone Is Insufficient

Senior living facilities operate in a workforce environment characterized by high turnover, reliance on contingent labor, and the constant pressure to maintain adequate staffing ratios. These dynamics make continuous monitoring senior care staff not merely a regulatory box to check but an operational imperative.

Turnover and Workforce Churn

Annual turnover rates for certified nursing assistants in nursing homes frequently exceed 50%, and in some markets approach or surpass 100%. This means that a facility with 50 CNA positions may hire 50 to 100 or more individuals per year to maintain staffing levels. Each new hire represents a potential risk if post-hire monitoring is absent.

An employee who passes a pre-hire background check may be arrested or convicted of a disqualifying offense weeks or months later. Without continuous monitoring, the facility remains unaware until the next scheduled re-screening, if one occurs at all.

Credential Lapses and License Expirations

Healthcare credentials require periodic renewal. A nurse aide who fails to complete required continuing education or pay renewal fees may fall off the state registry without the facility's knowledge. A licensed nurse whose license lapses due to unpaid fees or failure to meet renewal requirements may continue working if the facility does not verify credentials regularly.

Continuous monitoring systems that track credential status can alert administrators immediately when a license or certification becomes inactive. This allows the facility to remove the individual from the schedule and avoid regulatory violations.

Elder Abuse Risk Factors and How Screening Intersects with Prevention

Elder abuse represents a persistent and underreported crisis in senior living settings. Physical abuse, emotional abuse, financial exploitation, and neglect cause profound harm to individuals who often cannot advocate for themselves or report mistreatment.

| Abuse Type | Common Indicators | Screening Role |

| Physical Abuse | Unexplained injuries, bruising, rough handling | Detects prior assault or battery convictions |

| Financial Exploitation | Unauthorized withdrawals, coerced financial changes | Identifies theft, fraud, or exploitation convictions |

| Emotional Abuse | Verbal assaults, threats, humiliation | May reveal harassment or threatening behavior history |

| Neglect | Unmet hygiene, nutrition, or medical needs | Flags prior neglect findings in abuse registries |

Studies by government agencies and academic researchers have documented that elder abuse and neglect occur in institutional settings, though prevalence rates vary widely depending on definitions, reporting mechanisms, and study methodology. Background checks and continuous monitoring cannot prevent all forms of abuse, but they can detect individuals with documented histories of harm.

Screening as a Detection Layer

Criminal convictions for assault, battery, theft, fraud, or abuse-related offenses provide objective evidence of elevated risk. Abuse registry records document substantiated findings by protective services agencies. Exclusion lists identify individuals removed from healthcare settings due to misconduct. Screening serves as a gatekeeper, reducing the likelihood that individuals with known risk factors gain access to vulnerable populations.

Staffing Agency and Contingent Worker Screening Gaps

Many senior living facilities rely on staffing agencies to provide temporary nurses, nursing assistants, and other personnel during periods of high census, staff illness, or turnover. This reliance introduces screening gaps that facilities must address to maintain compliance and safety.

Contracts between facilities and staffing agencies often lack clear language specifying which party bears responsibility for background checks, exclusion list verification, and credential validation. Agencies may conduct minimal screening or rely on outdated checks. Facilities may assume the agency has completed all required due diligence, only to discover during a licensing survey that agency-provided staff were never properly screened.

Legal Accountability Rests with the Facility

Regardless of contractual language, state licensing agencies and CMS hold facilities accountable for ensuring all staff meet screening and credentialing requirements. A facility cannot delegate this obligation to a third party and avoid liability for non-compliance.

Administrators should require agencies to provide documentation of completed background checks, exclusion list searches, abuse registry checks, and credential verifications for each worker before that individual begins a shift. Facilities should verify this documentation independently and maintain copies in compliance files. Continuous monitoring should extend to agency staff, travel workers, and per-diem employees.

Licensing, Accreditation, and Audit Readiness

State licensing surveys, CMS certification surveys, and accreditation reviews examine whether facilities comply with nursing home employee background checks and credentialing requirements. Deficiencies in this area can result in citations, corrective action plans, fines, and threats to licensure or certification.

What Surveyors Look For

Surveyors review personnel files to confirm that background checks, exclusion list searches, and credential verifications occurred before hire and, where required, at specified intervals thereafter. They assess whether the facility has policies and procedures governing screening, how those policies are implemented, and whether documentation supports compliance.

Surveyors may select a sample of employee files and check whether individuals appear on exclusion lists or abuse registries. If a surveyor identifies an excluded or disqualified individual on staff, the facility faces immediate jeopardy findings and potential loss of participation in federal healthcare programs.

Continuous Monitoring as an Audit Strategy

Facilities that implement continuous monitoring senior care staff can demonstrate to surveyors that they have proactive systems in place to detect issues between formal re-screening cycles. Documentation showing regular exclusion list checks, automated alerts, and timely responses to flagged records strengthens the facility's compliance posture. Administrators should maintain logs showing when checks were conducted, what databases were searched, and how alerts were resolved.

Implementation Considerations: Operationalizing Monitoring in a High-Turnover Environment

Implementing a continuous monitoring program requires integration with existing HR systems, allocation of staff time for alert triage, and workflows that scale with facility size and complexity.

Technology Integration

Continuous monitoring systems typically integrate with applicant tracking systems or human resources information systems. Integration allows automatic enrollment of new hires into monitoring queues and removal of terminated employees. Facilities that lack integrated systems may need to manually upload employee rosters periodically.

Administrators should evaluate whether a monitoring service checks all required databases for their state, how frequently searches run, and whether the service provides alerts via email, dashboard, or API.

Alert Triage and Adjudication Workflows

Continuous monitoring generates alerts when new records appear. Not all alerts indicate disqualifying issues. An alert may reflect a case of mistaken identity, a non-disqualifying offense, or a matter that requires individualized assessment.

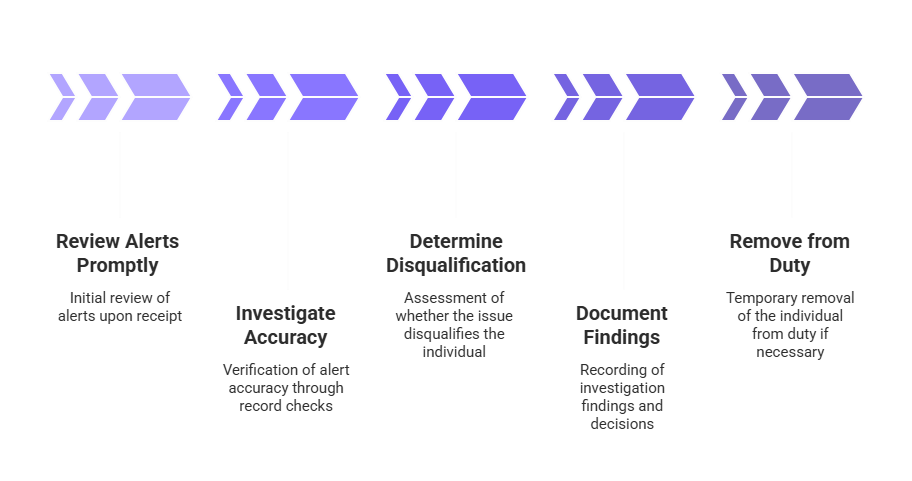

Facilities need clear protocols for:

- Reviewing alerts promptly upon receipt

- Investigating accuracy through record verification

- Determining whether the issue is disqualifying under applicable law

- Documenting investigation findings and decisions reached

- Removing individuals from duty when necessary pending resolution

Smaller facilities may assign alert review to the administrator or HR director. Larger organizations may designate compliance officers or legal staff to handle adjudication.

Resource Considerations for Small vs. Large Operators

| Facility Size | Monitoring Benefits | Implementation Considerations |

| Small Facilities (< 100 beds) | Reduces manual re-screening burden; provides automated alerts | Must ensure capacity to investigate alerts promptly |

| Large Operators (Multiple facilities) | Standardizes processes across locations; ensures consistency | Requires enterprise-level policies accounting for state-specific requirements |

Documentation should be readily accessible during licensing surveys and audits. Facilities should maintain records showing when each employee was enrolled in continuous monitoring, what databases are checked, when alerts were generated, and how alerts were resolved.

Common Misconceptions and Costly Assumptions

Misunderstandings about nursing home employee background checks and continuous monitoring lead to compliance gaps and preventable incidents. Recognizing these misconceptions helps administrators avoid costly errors.

"We Already Do Background Checks, So We're Covered"

Pre-hire background checks satisfy initial screening requirements but do not address post-hire risks. Employees may be arrested, convicted, excluded, or lose credentials after hire. Facilities that conduct only pre-hire checks operate with significant blind spots.

"The Staffing Agency Handles That"

Facilities remain legally responsible for ensuring all staff, including agency workers, meet screening requirements. Delegating this responsibility to an agency does not transfer liability. Administrators must verify that agencies conduct adequate checks and should independently confirm critical verifications.

"We Only Need to Check Clinical Staff"

While clinical staff such as nurses and nursing assistants have the most direct resident contact, other positions also require screening. Dietary staff, housekeeping staff, maintenance workers, and administrative personnel may have unsupervised access to residents or their belongings. Many state regulations require background checks for all employees with access to residents or resident living areas.

"A Clean Background Check Means Zero Risk"

Background checks detect only documented records. Individuals without prior convictions or registry entries may still pose risks. Screening is one component of a broader risk management strategy that must include training, supervision, reporting mechanisms, and responsive investigation of complaints.

"Federal Requirements Override State Requirements"

Federal conditions of participation set minimum standards for facilities participating in Medicare and Medicaid. State licensing laws may impose additional or more stringent requirements. Facilities must comply with both federal and state standards, applying the stricter standard when differences exist.

Conclusion

Continuous monitoring senior care staff has transitioned from an optional safeguard to a regulatory and operational baseline for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Administrators must understand what continuous monitoring entails, how it differs from pre-hire screening and periodic re-checks, and how to implement systems that align with federal and state requirements. Protecting vulnerable residents, maintaining compliance, and demonstrating audit readiness depend on proactive, ongoing oversight of all employees, including agency and contingent workers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between continuous monitoring and annual re-screening?

Continuous monitoring involves ongoing, automated checks of employee records, often daily or weekly, to detect new criminal activity, exclusions, or credential changes as they occur. Annual re-screening conducts background checks at fixed intervals, typically once per year, leaving months-long gaps during which changes go undetected.

Are nursing homes required by federal law to conduct continuous monitoring?

No single federal law explicitly mandates continuous monitoring for all nursing homes. However, CMS conditions of participation require facilities to ensure staff do not appear on federal exclusion lists, creating a practical need for regular checks. Many states have enacted laws requiring ongoing monitoring, and compliance obligations vary by jurisdiction.

What databases should be included in continuous monitoring for senior living staff?

At a minimum, continuous monitoring should include criminal history databases, sex offender registries, the OIG List of Excluded Individuals and Entities, the SAM exclusion records, state abuse and neglect registries, and state nurse aide and professional license databases. The specific databases required depend on state regulations and facility policies.

Who is responsible for the screening agency or temporary staff?

The senior living facility retains legal responsibility for ensuring all staff, including agency and temporary workers, meet screening and credentialing requirements. While agencies may conduct their own checks, facilities must verify that adequate screening occurred and should independently confirm key verifications to avoid compliance deficiencies.

How often should exclusion lists be checked?

Many compliance officers check federal and state exclusion lists monthly. Continuous monitoring systems can automate this process, checking lists as frequently as daily. The appropriate frequency depends on state requirements, facility risk tolerance, and the capabilities of the monitoring system in use.

Can continuous monitoring prevent all incidents of elder abuse?

No. Continuous monitoring detects individuals with documented histories of misconduct and alerts facilities to post-hire issues, but it cannot identify first-time offenders or individuals whose harmful behavior has not resulted in criminal or administrative records. Effective abuse prevention requires multiple strategies, including screening, training, supervision, reporting systems, and responsive management.

What should a facility do when a continuous monitoring alert is received?

The facility should immediately investigate the alert to verify its accuracy and determine whether the issue is disqualifying. If the alert involves mistaken identity, the facility should document the error. If the issue is confirmed and appears to preclude continued employment under applicable law and facility policy, the facility should consult legal counsel as appropriate, follow established procedures for addressing eligibility concerns, and document all actions taken.

Is continuous monitoring cost-effective for small facilities?

Yes. Continuous monitoring reduces the administrative burden of manual re-screening and provides automated alerts that help small facilities with limited staff stay compliant. The cost of monitoring is typically far lower than the potential fines, legal fees, and reputational harm resulting from employing disqualified individuals or failing licensing surveys.

Additional Resources

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Conditions of Participation for Long Term Care Facilities

https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/som107ap_pp_guidelines_ltcf.pdf - Office of Inspector General, List of Excluded Individuals and Entities

https://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/ - National Center on Elder Abuse, Elder Abuse Information

https://ncea.acl.gov/ - U.S. Department of Justice, National Sex Offender Public Website

https://www.nsopw.gov/ - System for Award Management (SAM) Exclusions

https://sam.gov/content/exclusions

GCheck Editorial Team

Meet the GCheck Editorial Team, your trusted source for insightful and up-to-date information in the world of employment background checks. Committed to delivering the latest trends, best practices, and industry insights, our team is dedicated to keeping you informed.

With a passion for ensuring accuracy, compliance, and efficiency in background screening, we are your go-to experts in the field. Stay tuned for our comprehensive articles, guides, and analysis, designed to empower businesses and individuals with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions.

At GCheck, we're here to guide you through the complexities of background checks, every step of the way.