Continuous monitoring for healthcare employees has transitioned from an emerging practice to a baseline compliance expectation, driven by tightened regulatory oversight, health system contract requirements, and escalating liability for negligent credentialing. Organizations that have not yet operationalized comprehensive post-hire monitoring programs face measurable exposure across regulatory, contractual, and legal dimensions.

Key Takeaways

- Continuous monitoring tracks criminal records, license status, and exclusion list changes in real time after hire, differing fundamentally from periodic rescreening or one-time checks.

- CMS Conditions of Participation, Joint Commission standards, and state-specific regulations create overlapping compliance obligations that vary by role and jurisdiction.

- Healthcare staffing agencies and health systems share liability for negligent credentialing, negligent hiring, and negligent retention when post-hire record changes go undetected.

- Role-specific monitoring protocols are required because clinical staff with direct patient access carry different risk profiles than administrative personnel.

- Multi-state operations introduce layered compliance complexity, requiring monitoring aligned with licensure state, placement state, and agency domicile state requirements.

- Common failure modes include conflating annual rescreening with continuous monitoring and assuming OIG exclusion checks alone satisfy monitoring obligations.

- Business cases for continuous monitoring center on quantifying the cost of compliance failures, contract losses, and adverse event responses rather than operational efficiency alone.

- Implementation requires integration with HRIS and credentialing systems, defined alert workflows, and documented escalation protocols for record changes.

What Continuous Monitoring Means in Healthcare Staffing

Continuous monitoring for healthcare employees refers to the systematic, automated tracking of specific data sources after an individual is hired or placed, designed to detect changes in criminal records, professional license status, and regulatory exclusion lists. This differs from point-in-time background checks conducted before hire and from periodic rescreening conducted at fixed intervals such as annually.

The distinction matters because regulatory bodies and health system clients increasingly expect real-time awareness of post-hire record changes. A nurse may pass an initial background check but subsequently face a DUI arrest, license suspension, or placement on a state abuse registry. Traditional annual rescreening creates a gap of up to 12 months during which the employer or staffing agency remains unaware of disqualifying events.

Continuous monitoring does not replace initial background checks. It functions as an ongoing compliance layer that extends the visibility window from a single point in time to the full duration of employment or contract engagement. It also does not replace clinical credentialing, privileging, or competency verification processes, which assess qualifications and clinical skills rather than legal eligibility to work.

Distinguishing Continuous Monitoring from Similar Processes

Ambiguity often arises when organizations describe their programs. Some use "continuous monitoring" to refer to quarterly or semi-annual rescreening, which does not meet the standard that regulators and clients increasingly expect. Genuine continuous monitoring involves:

- Automated queries against relevant databases, typically daily or weekly

- Real-time or near-real-time alerts when a monitored record changes

- Integration with employment and credentialing systems

- Documented workflows for reviewing and acting on alerts

Hospital Employee Monitoring Compliance

Hospitals and health systems conduct continuous background checks on employees in roles that meet specific risk thresholds, particularly those with direct patient contact, access to controlled substances, or responsibility for vulnerable populations. Whether a hospital monitors all employees continuously depends on its internal risk assessment, state law, and applicable accreditation standards. However, the expectation that hospitals will monitor contracted or temporary staff provided by staffing agencies has become standard in vendor compliance frameworks.

Regulatory Landscape: Federal, Accreditation, and State Requirements

Multiple regulatory bodies impose overlapping obligations that create a baseline floor for continuous monitoring programs. Federal agencies, accreditation organizations, and state regulators each contribute requirements that organizations must satisfy simultaneously.

CMS Conditions of Participation Background Checks

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Conditions of Participation require background checks for certain healthcare providers and suppliers. While CMS does not explicitly mandate continuous monitoring for all facility types, organizations subject to CMS Conditions of Participation are increasingly expected to demonstrate ongoing verification of employee eligibility, particularly for workers in home health, hospice, and long-term care settings.

For home health agencies, 42 CFR § 484.80 requires a comprehensive background check that includes state criminal history checks and verification against federal and state exclusion databases. Although the regulation specifies initial checks, CMS surveyors increasingly assess whether agencies have processes to detect post-hire changes, particularly regarding exclusion list status. Compliance requires that providers ensure employees remain free from disqualifying criminal convictions and exclusions throughout their tenure, though the specific methodology is not prescribed.

Joint Commission Standards

The Joint Commission's Human Resources standards require healthcare organizations to conduct background checks as part of the hiring process and to have a process for ongoing monitoring of staff competency and compliance with organizational policies. While the standards do not prescribe a specific monitoring frequency or methodology, Joint Commission surveys may assess whether organizations have processes to detect post-hire criminal convictions or license sanctions.

Organizations seeking to meet Joint Commission expectations operationalize continuous monitoring as evidence of a systematic compliance process rather than relying on passive measures such as self-reporting by employees.

OIG and GSA Exclusion List Obligations

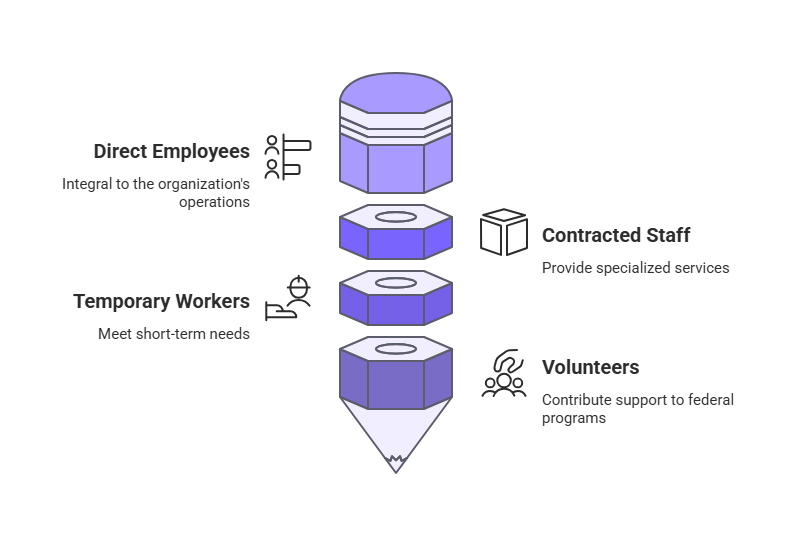

Federal law prohibits employing individuals on the Office of Inspector General (OIG) List of Excluded Individuals and Entities (LEIE) or the General Services Administration (GSA) System for Award Management (SAM) exclusion list in roles where services are billed to federal healthcare programs. This obligation is absolute and applies to:

- Direct employees

- Contracted staff

- Temporary workers provided by staffing agencies

- Volunteers whose services are billed to federal programs

Initial checks alone do not satisfy this requirement because exclusions can occur at any time due to fraud convictions, license revocations, or program integrity violations. Healthcare organizations and staffing agencies must conduct ongoing checks, typically monthly at minimum, to ensure no monitored individual has been added to an exclusion list. Failure to detect and act on an exclusion can result in overpayment recoupment, civil monetary penalties, and loss of Medicare billing privileges.

State-Level Monitoring Requirements

State regulations introduce variability in post-hire criminal monitoring healthcare requirements. Some states mandate continuous or periodic rescreening for specific healthcare roles, while others require monitoring only for employees in certain care settings.

State requirements vary significantly. For example, California Health and Safety Code § 1338.5 requires licensed home health agencies to conduct criminal background checks every two years for certain personnel. Massachusetts requires elder care facilities to recheck employees against the state abuse registry at intervals defined by regulation. Colorado mandates ongoing monitoring of nurse aides working in certified facilities. These examples are illustrative only and do not represent the full scope of state-specific requirements. Organizations must verify obligations in each jurisdiction where they operate.

Requirements differ not only by state but also by occupational category, creating complexity for staffing agencies that place workers across multiple jurisdictions and role types.

Role-Specific Monitoring Requirements

Healthcare staffing compliance requirements by state and by role create a matrix of obligations that cannot be satisfied with a uniform monitoring approach. Different roles carry different risk profiles, and regulatory expectations scale accordingly.

The following table illustrates monitoring approaches commonly adopted by healthcare organizations and reflects general regulatory expectations. It does not constitute legal advice and does not replace consultation with legal or compliance counsel. Actual requirements vary based on applicable federal and state laws, accreditation standards, client contracts, and organizational risk assessments. Organizations must independently verify obligations for their specific operations.

| Role Category | Monitoring Focus | Typical Frequency | Primary Regulatory Drivers |

| Registered Nurses (RN) | Criminal records, license status, exclusion lists, controlled substance registrations | Continuous (daily/weekly) | State nursing boards, CMS, DEA, OIG |

| Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN) | Criminal records, license status, exclusion lists | Continuous (daily/weekly) | State nursing boards, CMS, OIG |

| Certified Nursing Assistants (CNA) | Criminal records, certification status, abuse registries, exclusion lists | Continuous (daily/weekly) | State certification bodies, abuse registries, CMS |

| Therapists (PT, OT, SLP) | License status, exclusion lists, criminal records | Continuous or monthly | State licensure boards, OIG |

| Physicians and Advanced Practice Providers | License status, DEA registration, board actions, exclusion lists, malpractice sanctions | Continuous (daily/weekly) | State medical boards, National Practitioner Data Bank, OIG, DEA |

| Allied Health (e.g., radiology, respiratory) | Certification status, license (if applicable), exclusion lists | Monthly to continuous | Certifying bodies, state agencies, OIG |

| Administrative and Non-Clinical Staff | Exclusion lists, criminal records (if access to patient data or vulnerable populations) | Monthly to quarterly | OIG, organizational policy |

Clinical Staff Monitoring Intensity

Nurses with direct patient contact and responsibility for medication administration require the most intensive monitoring. License boards update disciplinary actions and suspensions regularly, and delays in detecting these changes can result in an unqualified individual providing care. Similarly, placement on a state nurse aide abuse registry disqualifies an individual from working in certified facilities, and continued employment after such placement constitutes a compliance violation.

Administrative Staff Considerations

Administrative staff generally require less intensive monitoring unless they handle protected health information or have unsupervised access to vulnerable patients. However, exclusion list monitoring applies universally to any role where services may be billed to federal programs, including billing specialists and coders.

The Liability Framework: Negligent Credentialing, Hiring, and Retention

Healthcare organizations and staffing agencies face legal exposure when employees or contractors with disqualifying backgrounds cause harm. Three doctrines define this exposure: negligent hiring, negligent credentialing, and negligent retention.

Negligent hiring occurs when an employer fails to conduct reasonable pre-employment screening and subsequently hires an individual whose background presented foreseeable risk. This doctrine applies to the initial hiring decision and the adequacy of the background check conducted before placement.

Negligent credentialing applies specifically to healthcare settings where an organization grants clinical privileges or credentials an individual to provide patient care without verifying qualifications, license status, or disciplinary history. Continuous monitoring directly mitigates negligent credentialing risk by ensuring that credentials remain valid and unencumbered throughout the engagement.

Negligent retention occurs when an employer becomes aware, or should have become aware, of an employee's unfitness for a role but fails to take corrective action. This is the liability most directly addressed by continuous monitoring.

The "Should Have Known" Standard

If a staffing agency places a nurse whose license is subsequently suspended, and the agency had no system to detect the suspension, the agency may face negligent retention liability if the nurse causes patient harm during the period of suspension. The "should have become aware" standard is applied by courts to assess whether a reasonable employer in the same industry would have had processes in place to detect a disqualifying event.

As continuous monitoring adoption increases in healthcare staffing, organizations relying solely on annual rescreening or self-reporting may face scrutiny regarding whether their processes met reasonable diligence standards. Organizations should consult legal counsel to assess their specific risk exposure.

Shared Liability Between Agencies and Health Systems

Liability is not borne solely by the staffing agency or solely by the hospital. Both entities may be named in litigation, and contractual indemnification clauses do not eliminate the need for each party to maintain defensible monitoring processes. Health systems increasingly require proof of continuous monitoring in vendor contracts, shifting some compliance burden to staffing agencies but retaining their own duty to verify that contract staff remain qualified.

Operational Implementation: Building a Continuous Monitoring Program

A functional continuous monitoring program requires more than vendor selection. It requires integration with internal systems, defined workflows, and documented policies that specify how alerts are handled.

Data Sources Monitored

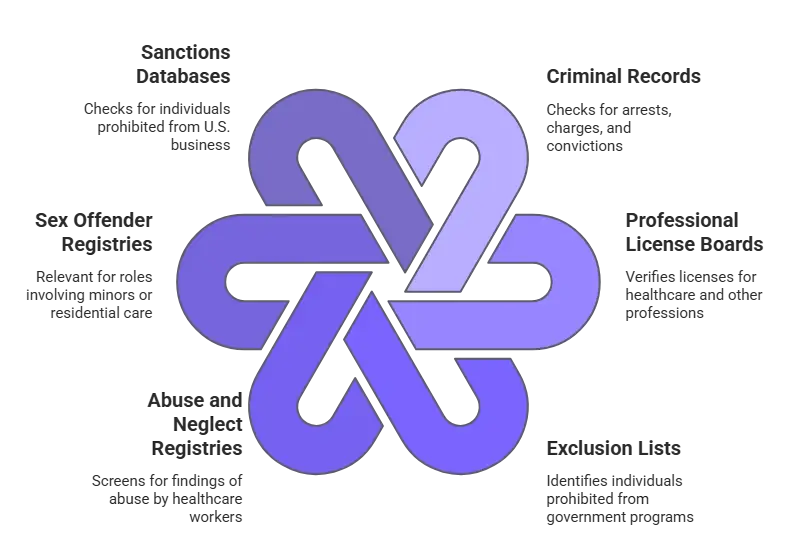

A comprehensive program queries multiple databases:

- Criminal records: County, state, and federal criminal databases to detect arrests, charges, and convictions

- Professional license boards: State boards for nursing, medicine, therapy, and other licensed professions

- Exclusion lists: OIG LEIE, GSA SAM, and state Medicaid exclusion lists

- Abuse and neglect registries: State-level registries for healthcare worker abuse findings

- Sex offender registries: Relevant for roles with access to minors or certain residential care settings

- Sanctions databases: Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for individuals prohibited from conducting business in the U.S.

Note that continuous monitoring typically tracks court records, not arrests alone, as arrest data may not indicate a disqualifying event until adjudication. Monitoring detects suspensions, revocations, probationary status, and disciplinary actions from license boards. Checks should occur at least monthly, though best practice is weekly or more frequent.

Integration with HRIS and Credentialing Systems

Continuous monitoring data must flow into the systems where staffing and compliance decisions are made. Integration with Human Resources Information Systems (HRIS) ensures that alerts trigger immediate review and, if necessary, suspension of work assignments.

For staffing agencies, integration with vendor management systems (VMS) or applicant tracking systems (ATS) allows automated hold placement when an alert is generated. Without integration, alerts may be received but not acted upon promptly, undermining the purpose of continuous monitoring. Credentialing systems used by hospitals and health systems should reflect the monitoring status of contracted staff.

Alert Workflows and Escalation Protocols

An alert indicating a record change does not automatically disqualify an individual. Organizations must establish workflows that define:

| Workflow Element | Requirements |

| Alert Recipients | Compliance managers, HR directors, or designated credentialing staff |

| Initial Review Criteria | Determining whether the alert represents a disqualifying event under organizational policy and applicable law |

| Escalation Procedures | Who makes the decision to suspend, terminate, or remove an individual from assignment, and within what timeframe |

| Documentation Requirements | All alerts, review decisions, and actions taken must be documented for audit and litigation defense purposes |

Failure to act on an alert within a reasonable timeframe can negate the compliance value of the monitoring program. A staffing agency that receives an alert about a nurse's license suspension but allows the nurse to continue working for several days pending review has not adequately mitigated negligent retention risk.

Internal Policy Documentation

Organizations must document their continuous monitoring policies, including:

- Scope (which roles are monitored)

- Frequency (daily, weekly, monthly by data source)

- Response protocols

- Compliance responsibilities

This documentation serves as evidence of due diligence in regulatory audits and legal proceedings. Policies should specify the criteria for disqualifying events. Not all criminal convictions or license actions warrant termination, and policies should reflect relevant legal standards such as whether a conviction is directly related to job duties or occurred within a state-defined lookback period.

State-by-State Variance and Multi-State Compliance Complexity

Healthcare staffing agencies operating across state lines face compliance obligations that vary by licensure state, placement state, and agency domicile state. This layered structure creates jurisdictional challenges that require systematic decision frameworks.

Three-Jurisdiction Framework

Healthcare staffing agencies operating across state lines face compliance obligations that vary by:

- Licensure state: The state where the employee holds a professional license

- Placement state: The state where the employee is assigned to work

- Agency domicile state: The state where the staffing agency is headquartered or registered

Travel nurses and locum tenens providers exemplify this complexity. A nurse licensed in California, placed by an agency based in Florida, and working at a hospital in Texas must be monitored according to California nursing board actions, Texas employment law requirements, and Florida agency obligations.

Compact Licensure Considerations

If the nurse holds compact licensure under the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC), disciplinary actions in the home state may affect practice privileges in all compact states, requiring monitoring systems that recognize multi-state license dependencies.

Lookback Periods and Ban-the-Box Laws

Criminal history lookback periods vary by state and often include exceptions based on role type or offense severity. For example, California law limits consideration of certain criminal convictions to seven years in many employment contexts, though exceptions may apply for healthcare positions or certain offenses. New York has no general statutory lookback limit. Organizations must verify specific requirements applicable to their operations and should consult legal counsel when multi-state requirements conflict.

Ban-the-box laws in some jurisdictions restrict when and how employers may inquire about criminal history. These laws typically apply to initial hiring decisions but may also affect continuous monitoring practices, particularly regarding how alerts are handled and communicated.

Decision Framework for Multi-State Operations

Organizations managing multi-state operations require decision frameworks rather than exhaustive state-by-state checklists. A framework approach involves:

- Identifying all jurisdictions where the organization places workers

- Determining which jurisdiction's law applies to specific compliance questions

- Applying the most restrictive standard when laws conflict or overlap

- Documenting the rationale for decisions when state laws diverge

Healthcare staffing compliance requirements by state also govern whether and how arrest records, as opposed to convictions, may be considered. Some states prohibit adverse action based on arrest without conviction unless the conduct is directly job-related and recent.

Common Failure Modes and Misconceptions

Several operational misunderstandings undermine the effectiveness of monitoring programs and expose organizations to preventable risk. Recognizing these failure patterns helps organizations avoid implementing programs that appear compliant but lack practical effectiveness.

Conflating Rescreening with Continuous Monitoring

Misconception: Annual rescreening equals continuous monitoring.

Rescreening at fixed intervals, even quarterly, does not satisfy the definition of continuous monitoring. A nurse whose license is suspended three months after an annual recheck will work with an invalid license until the next scheduled recheck. Continuous monitoring detects the suspension within days.

Overreliance on Exclusion List Checks

Misconception: OIG exclusion checks alone constitute a complete program.

Exclusion list monitoring is mandatory but insufficient. An individual may have a disqualifying criminal conviction or suspended license without being excluded from federal programs. Focusing only on exclusion lists leaves critical gaps.

Misallocating Responsibility

Misconception: The hospital bears all monitoring responsibility for contracted staff.

Health systems expect staffing agencies to maintain continuous monitoring programs as a baseline contract requirement. While hospitals may conduct their own parallel monitoring, agencies that assume hospitals will detect post-hire issues face contract termination and liability exposure.

Relying on Self-Reporting

Misconception: Self-reporting by employees is a reliable monitoring method.

Policies requiring employees to report arrests, convictions, or license actions are necessary but not sufficient. Many employees fail to self-report due to fear of job loss or lack of awareness that an event is reportable. Continuous monitoring provides an independent verification layer.

Limiting Monitoring to Clinical Staff

Misconception: Monitoring is only necessary for clinical staff.

Non-clinical staff with access to patient records or vulnerable individuals also require monitoring, particularly for exclusion list status and, depending on role, criminal history. Billing and coding staff whose services are billed to Medicare must be free from exclusions.

Alert Management Failures

Failure mode: Receiving alerts but not acting on them promptly.

Technology that generates alerts without integrated workflows creates a false sense of compliance. Alerts must be reviewed, triaged, and acted upon within timeframes that prevent individuals from continuing in disqualifying roles.

Ignoring License Status

Failure mode: Monitoring only criminal records and ignoring license status.

License boards take disciplinary actions that may not result in criminal charges but that disqualify individuals from practice. A nurse on probation with prescribing restrictions may not have a criminal record but cannot work in roles requiring medication administration.

ROI and Business Case: Quantifying Continuous Monitoring Investment

Building a business case for continuous monitoring requires quantifying the costs of non-compliance rather than asserting generalized efficiency gains. Decision-makers need frameworks that connect program investment to measurable risk reduction.

Cost of a Negligent Credentialing Claim

Healthcare negligent credentialing claims result in settlements and judgments that vary widely based on severity of harm, jurisdiction, and insurance coverage. Organizations should consult legal counsel and insurance carriers to estimate potential exposure specific to their risk profile.

Factors that increase exposure include:

- Facility type (acute care vs. outpatient vs. long-term care)

- Patient acuity levels

- History of compliance findings

- Prior litigation or settlement history

Cost of Regulatory Non-Compliance

CMS can impose civil monetary penalties for Conditions of Participation violations. Joint Commission findings can result in accreditation downgrades or loss, affecting Medicare billing eligibility. State health departments can levy fines, impose corrective action plans, or suspend licenses for facilities that employ individuals with disqualifying backgrounds.

Organizations should calculate the cost of a single survey finding, including:

- Remediation time and staff diversion

- Consultant fees for corrective action plans

- Legal review and documentation costs

- Potential loss of referrals during corrective action periods

Cost of Contract Loss

Health systems increasingly terminate staffing vendor relationships over compliance gaps. The cost of losing a major hospital client includes not only lost revenue from that contract but also reputational damage that affects new business development. Continuous monitoring programs serve as competitive differentiators in RFP responses and vendor compliance reviews.

Cost of Adverse Event Response

When an employee with a disqualifying background causes patient harm, the organization incurs costs for:

- Internal investigation and root cause analysis

- Legal defense and potential settlement or judgment

- Regulatory reporting and survey response

- Increased insurance premiums

- Damage to organizational reputation

A business case framework compares the annual cost of a continuous monitoring program (vendor fees, integration costs, staff time for alert review) against the estimated cost of a single compliance failure. Organizations should work with legal counsel, insurance advisors, and financial professionals to assess their specific risk profile and exposure.

Decision Framework: Evaluating Readiness and Selecting an Approach

Organizations assessing their current monitoring maturity can use a staged framework to identify gaps and prioritize improvements. This maturity model helps organizations understand where they are and what steps are required to reach defensible compliance.

Monitoring Maturity Stages

The following framework illustrates one approach organizations use to assess monitoring program maturity. It is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute a compliance requirement or legal recommendation. Organizations should assess their specific obligations with legal and compliance counsel.

| Stage | Description | Risk Profile | Common Next Steps |

| Stage 0: No post-hire monitoring | Reliance on initial background checks only | Highest risk | Implement exclusion list monitoring immediately |

| Stage 1: Periodic rescreening | Annual or semi-annual background checks at fixed intervals | High risk, gaps of up to 12 months | Add continuous exclusion and license monitoring |

| Stage 2: Partial continuous monitoring | Continuous monitoring of exclusion lists only, with periodic rescreening for criminal and license checks | Moderate risk, federal requirements met but state/accreditation gaps may remain | Expand to license and criminal record monitoring for clinical roles |

| Stage 3: Comprehensive continuous monitoring | Automated, continuous monitoring of all required data sources, integrated with HRIS, with documented alert workflows | Best practice, defensible compliance posture | Optimize workflows, ensure documentation rigor |

Organizations at Stage 0 or Stage 1 should prioritize exclusion list monitoring first, as this addresses absolute federal compliance obligations. License monitoring should follow for clinical roles, as license suspensions create immediate practice barriers. Criminal record monitoring completes the program for roles where criminal history is a disqualifying factor.

Evaluation Criteria for Program Selection

When evaluating continuous monitoring approaches, organizations should assess:

- Data source coverage: Does the solution monitor all required databases for your role mix and jurisdictions?

- Update frequency: How often are data sources queried? Daily and weekly monitoring is standard for clinical roles.

- Integration capabilities: Can the solution integrate with your HRIS, VMS, or credentialing system via API or automated data feeds?

- Alert quality: Does the solution provide context for alerts, or does it generate high volumes of false positives requiring manual review?

- Compliance documentation: Does the solution provide audit trails and compliance reports suitable for regulatory review and client audits?

- Multi-state functionality: If you operate across state lines, does the solution accommodate varying state requirements without requiring separate contracts or configurations?

- Scalability: Can the solution accommodate workforce growth without requiring process redesign?

Organizations should also assess internal readiness. A monitoring program requires staff capacity to review alerts, make disqualification decisions, and document actions taken. Technology alone does not constitute a program.

Conclusion

Continuous monitoring for healthcare employees is no longer optional infrastructure. Regulatory bodies expect it, health system clients require it, and liability exposure for its absence has become material. Organizations that have not yet operationalized comprehensive monitoring programs should prioritize exclusion list and license monitoring first, followed by criminal record monitoring based on role risk profiles. The question is no longer whether to implement continuous monitoring, but how rapidly and comprehensively to close existing gaps.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between continuous monitoring and rescreening?

Continuous monitoring involves automated, ongoing queries of criminal, license, and exclusion databases, typically daily or weekly, with real-time alerts when records change. Rescreening occurs at fixed intervals such as annually and creates gaps between checks. Continuous monitoring detects changes within days rather than months.

Do all healthcare employees require continuous monitoring?

Requirements vary by role, state, and employer policy. Clinical staff with direct patient contact, controlled substance access, or work with vulnerable populations typically require the most intensive monitoring. Non-clinical staff require at minimum exclusion list monitoring if their services are billed to federal programs.

How do multi-state staffing agencies manage varying state requirements?

Multi-state agencies must monitor compliance obligations in the licensure state, placement state, and agency domicile state. A decision framework approach applies the most restrictive standard when laws conflict. Systems capable of accommodating state-specific lookback periods, ban-the-box rules, and reporting requirements are necessary for scalable multi-state operations.

What happens when a continuous monitoring alert is received?

Alerts must be reviewed to determine whether the event is disqualifying under organizational policy and law. Disqualifying events typically require immediate suspension of the individual from work assignments pending investigation. Non-disqualifying events are documented but may not require action.

Is continuous monitoring required by CMS?

CMS Conditions of Participation require initial background checks for certain provider types and ongoing verification that employees remain free from exclusions. While CMS does not explicitly mandate continuous monitoring for all settings, surveyors assess whether organizations have processes to detect post-hire changes. Organizations should consult compliance counsel to determine applicable requirements for their specific operations.

Can organizations rely on employee self-reporting instead of continuous monitoring?

Self-reporting policies are necessary but not sufficient. Many employees fail to report disqualifying events due to fear of job loss or unawareness of reporting obligations. Continuous monitoring provides independent verification and is increasingly viewed as a reasonable diligence standard in healthcare staffing.

What is the typical cost of a continuous monitoring program?

Costs vary based on workforce size, role mix, data sources monitored, and vendor. Organizations should calculate cost relative to the potential expense of a single compliance failure, including regulatory penalties, contract loss, and negligent credentialing liability.

How frequently should exclusion lists be checked?

Federal law requires that organizations not employ individuals on OIG or GSA exclusion lists in roles where services are billed to federal programs. Best practice is weekly or more frequent checks. Monthly checks represent the minimum defensible frequency.

Additional Resources

- CMS Conditions of Participation: Home Health Agencies

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-G/part-484 - Office of Inspector General List of Excluded Individuals and Entities

https://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/ - The Joint Commission Human Resources Standards

https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/standard-faqs/hospital-and-hospital-clinics/human-resources-hr/000001992/ - System for Award Management (SAM) Exclusions

https://sam.gov/content/exclusions - National Council of State Boards of Nursing: Nurse Licensure Compact

https://www.ncsbn.org/nurse-licensure-compact.htm - Federal Trade Commission: Background Checks Guidance

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/using-consumer-reports-what-employers-need-know

GCheck Editorial Team

Meet the GCheck Editorial Team, your trusted source for insightful and up-to-date information in the world of employment background checks. Committed to delivering the latest trends, best practices, and industry insights, our team is dedicated to keeping you informed.

With a passion for ensuring accuracy, compliance, and efficiency in background screening, we are your go-to experts in the field. Stay tuned for our comprehensive articles, guides, and analysis, designed to empower businesses and individuals with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions.

At GCheck, we're here to guide you through the complexities of background checks, every step of the way.