Understanding the distinction between federal and state criminal background checks is essential for employers conducting thorough pre-employment screenings. Each court system maintains separate records that require different search methods and access protocols. This guide explains how federal and state court dispositions differ, why jurisdiction matters for background screening, and how employers can ensure complete and compliant criminal record searches.

Key Takeaways

- Federal courts handle violations of federal law such as drug trafficking, immigration offenses, and white-collar crimes, while state courts process violations of state statutes including most violent crimes, theft, and DUIs.

- Criminal background checks do not automatically search both federal and state court systems simultaneously, requiring employers to conduct separate searches for comprehensive results.

- PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) provides access to federal court dispositions but does not include state-level criminal records, which must be obtained through county courthouses or state repositories.

- Approximately 90% of criminal cases are prosecuted at the state level, making state court searches essential for thorough background screening despite the serious nature of federal offenses.

- Employers must understand jurisdiction mapping to avoid gaps in background screening that could expose their organization to negligent hiring liability.

- FCRA compliance requires employers to follow specific procedures when using criminal records for employment decisions, regardless of whether the records originate from federal or state courts.

What Is the Difference Between Federal and State Courts?

The United States operates under a dual court system where federal and state courts function independently with distinct jurisdictions, types of cases, and record-keeping systems. Federal courts derive their authority from the U.S. Constitution and handle cases involving federal law violations, constitutional questions, and disputes between states. State courts operate under state constitutions and process the vast majority of criminal and civil cases within their geographic boundaries.

The jurisdiction where crimes are prosecuted determines which court system maintains the records and how employers can access disposition information. This separation creates potential gaps in background screening. A person's criminal history may exist in either court systemâor bothâdepending on the nature of their offenses.

Federal Court Jurisdiction and Case Types

Federal courts have limited jurisdiction and only hear cases falling under specific categories defined by federal law. Criminal cases in federal court typically involve violations of U.S. federal statutes, crimes committed on federal property, or offenses that cross state lines. These courts operate through 94 district courts, 13 circuit courts of appeals, and the Supreme Court.

Common federal criminal offenses include drug trafficking across state lines, immigration violations, white-collar crimes like securities fraud and tax evasion, federal weapons offenses, and terrorism charges. Federal prosecutions represent approximately 10% of all criminal cases but often involve more serious offenses with longer sentences. Employers in finance, healthcare, and government contracting should pay particular attention to federal court records due to regulatory violations prosecuted at this level.

State Court Jurisdiction and Case Types

State courts have broad jurisdiction and process approximately 90% of all criminal cases annually. These courts operate under state law and include trial courts, appellate courts, and state supreme courts. Each state maintains its own court structure, record-keeping systems, and access procedures.

State courts prosecute violations of state criminal statutes, encompassing most crimes that affect individuals and communities. Common cases include violent crimes, property crimes, drug offenses, traffic violations, and public order offenses. State court records are maintained at the county level, meaning employers must search individual county courthouses or use state repository databases. This decentralized system creates challenges for comprehensive background screening, especially for candidates who have lived in multiple counties or states.

How Federal vs State Criminal Background Checks Differ

When employers order criminal background checks, the scope and methodology vary significantly depending on whether they're searching federal or state court records. A standard criminal background check does not automatically include both systems, and many employers unknowingly create gaps by assuming a single search captures all relevant criminal history. Background screening companies typically offer federal and state searches as separate products with different pricing structures.

| Comparison Factor | Federal Criminal Background Checks | State Criminal Background Checks |

| Court System Coverage | 94 federal district courts nationwide | County-level courts across all states |

| Access Method | PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) | County courthouses, state repositories, or databases |

| Types of Crimes | Drug trafficking, immigration, white-collar crimes, federal weapons, terrorism | Violent crimes, property crimes, DUI/DWI, local drug possession, assault, theft |

| Record Organization | Centralized, well-organized, digitized | Decentralized, varies by state and county |

| Search Requirements | Single PACER account for nationwide access | Multiple county searches based on address history |

| Typical Cost | $10-40 per search | $8-30 per county search |

| Turnaround Time | 1-3 business days | 1-2 days (online) to 3-7 days (manual) |

| Percentage of Cases | Approximately 10% of all prosecutions | Approximately 90% of all prosecutions |

Federal criminal background checks require accessing PACER or working with screening companies that have established federal court search protocols. State searches involve searching county-level court records, state repositories, or statewide databases. The specific counties must be identified based on where the candidate has lived, worked, or attended school during the relevant lookback period.

Access Methods and Search Procedures

Federal court dispositions are accessible through PACER, a centralized electronic system maintained by the federal judiciary providing nationwide access to federal court documents. Users create a PACER account and pay $0.10 per page for documents, with fees waived if quarterly charges don't exceed $30 as of 2025.

State criminal records require different access methods depending on jurisdiction, including county courthouse searches through online portals or manual research, state repository databases where available, and third-party aggregated databases. The decentralized nature of state record-keeping means employers must determine appropriate search locations based on a candidate's seven-year address history or longer depending on state law and position requirements.

Record Completeness and Reporting Timeframes

Federal court records are generally comprehensive and updated regularly within the PACER system, with most records from the past 25 years readily available electronically. State court records vary dramatically in completeness and currency depending on digitization levels.

| State Digitization Level | Record Access | Typical Turnaround |

| Highly Digitized | Online statewide systems | 1-2 business days |

| Partially Digitized | Mixed online/manual | 2-5 business days |

| Limited Digitization | Primarily manual courthouse | 5-10 business days |

Employers should be aware that state criminal records may have reporting delays of days to months depending on the jurisdiction's court administration efficiency, affecting screening turnaround times and conditional offer decisions.

Why Jurisdiction Matters for Background Screening

Jurisdiction determines which court system prosecutes a crime and maintains the resulting criminal records, directly impacting an employer's ability to discover relevant criminal history. Many employers mistakenly believe that ordering a "criminal background check" automatically searches all available records, but the search scope depends entirely on which jurisdictions are included. This misunderstanding creates dangerous gaps in screening coverage.

A candidate who has lived in five counties across three states over the past seven years requires searches in multiple jurisdictions to ensure complete coverage. Missing even one relevant jurisdiction could mean overlooking serious criminal history. Federal jurisdiction operates nationwide but only captures the small percentage of crimes prosecuted under federal law.

Geographic Coverage Considerations

State criminal background checks are inherently limited by geographic boundaries. Unlike credit reports or federal databases, there is no single comprehensive national criminal database capturing all state-level prosecutions. The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database exists but is only accessible to law enforcement, not private employers.

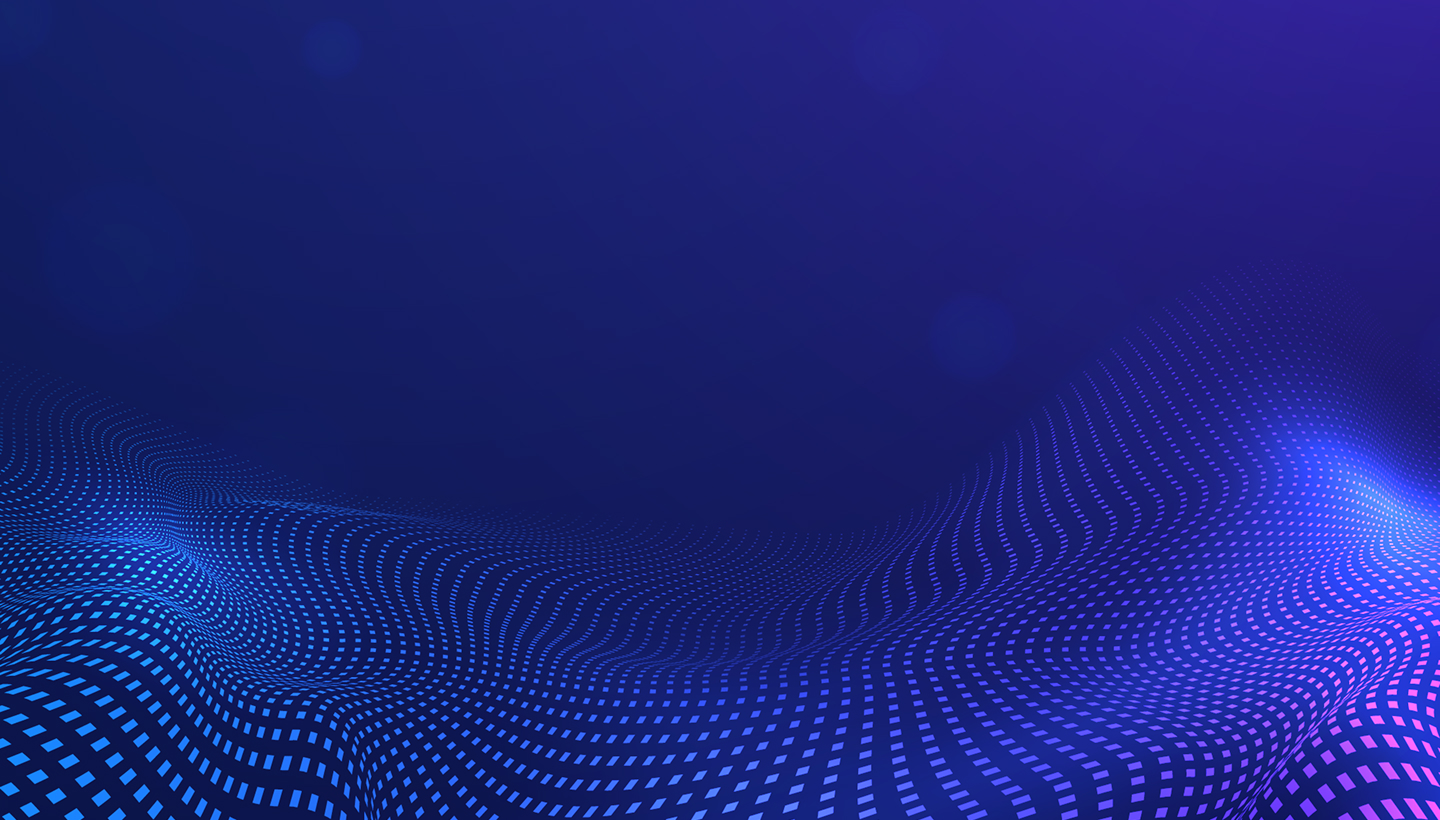

Employers must determine search locations based on several factors:

- Candidate-provided address history: Typically covering seven years, including all counties where the candidate has resided for six months or longer

- Work locations and educational institutions: Places where candidates spent significant time and may have had law enforcement encounters

- Common name considerations: Candidates with common names may require expanded searches to distinguish between individuals

- Position risk level: Higher-risk positions warrant more comprehensive geographic coverage, potentially including nearby counties or extended lookback periods

- State law requirements: Some states mandate specific search protocols or extended geographic coverage for regulated positions

Best practice recommendations suggest searching all counties where a candidate has lived for six months or longer during the lookback period.

Industry-Specific Jurisdiction Requirements

Certain industries face regulatory requirements that dictate the scope of criminal background check jurisdictions. Healthcare organizations, financial services firms, and government contractors often must comply with specific search protocols including both federal and state court searches.

Healthcare employers subject to state licensing requirements must often conduct state repository searches using fingerprints for licensed positions, federal court searches for positions with prescription drug access, and county-level searches in all candidate residence locations. Financial services firms regulated by FINRA or state banking authorities typically require comprehensive searches including federal courts to identify securities fraud, embezzlement, and other white-collar crimes. Government contractors must often comply with federal suitability standards mandating both federal and state criminal history searches for positions with security clearances or sensitive information access.

PACER Background Checks and Federal Court Access

PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) is the federal judiciary's centralized electronic public access service providing online access to case and docket information from federal appellate, district, and bankruptcy courts. For employers conducting background checks, PACER represents the primary method for searching federal criminal court dispositions and verifying federal criminal history.

The PACER system covers all 94 federal district courts, 13 circuit courts of appeals, and bankruptcy courts across the United States. Users can search by party name, case number, or other identifying information to locate criminal cases and dispositions. Registration is straightforward and free, with document access incurring charges of $0.10 per page (capped at $3.00 per document). Users who accumulate less than $30 in quarterly charges have fees waived, making occasional searches effectively free.

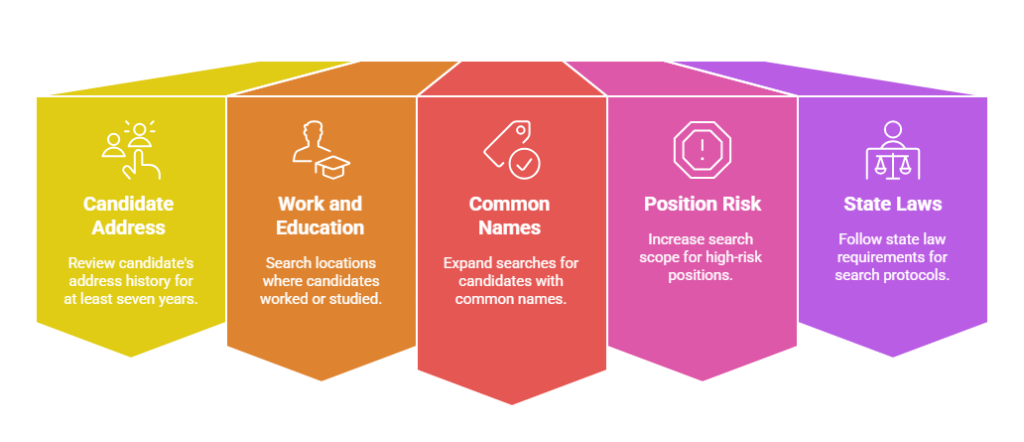

How to Search PACER for Criminal Records

Searching PACER requires understanding the system's structure and search capabilities to conduct effective federal criminal background searches. The PACER Case Locator is particularly valuable because it allows searches across all federal courts without knowing the specific district where a case might have been filed.

To conduct an effective PACER criminal background search, employers should follow these steps:

- Access the PACER Case Locator: Navigate to pacer.uscourts.gov, log in with credentials, and select the Case Locator option for nationwide searching

- Enter identifying information: Search using the candidate's full name, including aliases or name variations, along with date of birth if available

- Filter by case type: Select "criminal" to exclude civil and bankruptcy cases from search results

- Review results carefully: Examine results to confirm the case involves your candidate by checking case details, defendant information, and geographic location

- Access case documents: Review charging documents, plea agreements, and final dispositions to understand the nature and outcome of the case

- Use multiple identifiers: Include middle names, Social Security number portions, and known addresses to confirm identity when common names return numerous results

PACER searches work best with accurate identifying information including full legal name and approximate date of birth.

Limitations of PACER for Background Screening

While PACER provides comprehensive access to federal court records, it has important limitations. PACER only includes federal court cases and contains no state-level criminal records, county court information, or state repository data. An individual could have extensive state criminal history that would never appear in a PACER search.

Additional limitations include historical record gaps for cases filed before the mid-1990s, sealed records not being accessible, identity verification challenges with similar names, and no recent arrest information without formal charges. Employers should view PACER searches as one component of comprehensive background screening. Best practices involve combining federal court searches through PACER with county-level state court searches and state repository checks.

Creating a Comprehensive Background Check Strategy

Employers need a strategic approach combining federal and state criminal background checks to ensure complete coverage and minimize negligent hiring risks. A comprehensive strategy considers the position's responsibilities, industry requirements, and the candidate's geographic history. The foundation of comprehensive screening is understanding that no single search captures all criminal records.

Effective background check strategies typically include several components:

- County criminal searches: Direct courthouse searches in all counties where the candidate has lived during the lookback period (typically seven years)

- State repository checks: Statewide database searches where available and legally permissible, often using fingerprints for regulated positions

- Federal district court searches: PACER-based searches covering federal criminal prosecutions across all relevant federal districts

- National database searches: Supplemental searches of aggregated criminal databases to identify potential records, always verified at the source

This layered approach provides overlapping coverage that reduces the likelihood of missing relevant criminal history.

Risk-Based Search Scope Decisions

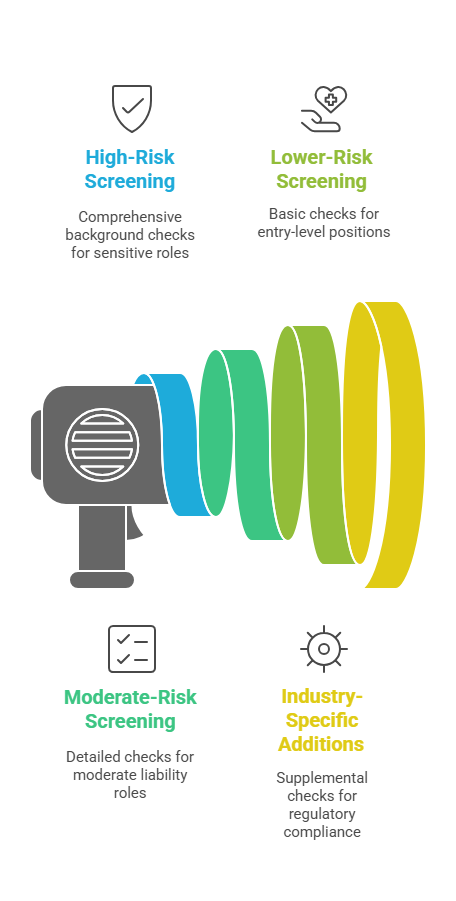

Not every position requires the same depth of criminal background screening. Employers should implement risk-based tiering that allocates screening resources proportionate to position-specific risks. This approach optimizes screening budgets while ensuring adequate coverage for positions with the greatest liability exposure.

Risk factors warranting more comprehensive federal and state searches include financial responsibility, vulnerable population access, security clearance requirements, licensed professions, and driving responsibilities. Positions with access to company funds require federal white-collar crime searches. Roles involving children, elderly individuals, or disabled persons demand thorough searches for relevant violent and sexual offenses.

Lower-risk positions such as entry-level roles without sensitive access might reasonably use county searches in recent residence locations with a national database check, without routine federal searches.

Timing and Turnaround Expectations

Understanding realistic turnaround times for federal versus state criminal background checks helps employers plan hiring timelines and manage candidate expectations. Search durations vary based on jurisdiction, search methods, and current court backlogs.

| Search Type | Typical Turnaround | Key Factors |

| Federal PACER Search | 1-3 business days | Name commonality, case volume |

| County Criminal (online) | 1-2 business days | Database availability |

| County Criminal (manual) | 3-7 business days | Courthouse access, records format |

| State Repository | 3-10 business days | State processing times |

| National Database | Instant-24 hours | Database completeness |

Employers should build these timeframes into their hiring process and issue conditional offers only after appropriate background check clearance. The most effective approach involves starting background checks early in the hiring process rather than waiting until a final decision has been made.

FCRA Compliance for Federal and State Criminal Records

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) establishes legal requirements that employers must follow when using criminal background check information for employment decisions. Compliance obligations apply equally to federal court dispositions obtained through PACER searches and state criminal records retrieved from county courthouses or state repositories.

FCRA compliance involves specific procedural steps before requesting background checks, during the screening process, and when taking adverse action. Many employers face litigation because they failed to follow proper FCRA procedures. The law prioritizes process and disclosure over the substantive use of criminal information.

Key FCRA requirements include obtaining written authorization on a standalone document before ordering background checks, providing pre-adverse action notice with a copy of the background check report and summary of FCRA rights, allowing a reasonable waiting period (typically 5-7 business days) for candidates to review the report and dispute inaccuracies, and providing final adverse action notice if proceeding with the negative decision.

Ban-the-Box and State-Specific Restrictions

Beyond federal FCRA requirements, employers must navigate a complex patchwork of state and local laws restricting how criminal records can be used in hiring decisions. More than 37 states and over 150 cities and counties have enacted "ban-the-box" laws limiting when employers can inquire about criminal history or how they can use criminal record information.

These laws vary significantly by jurisdiction but commonly include timing restrictions prohibiting criminal history questions on initial applications, individualized assessment requirements mandating consideration of the nature of the offense and relevance to the position, notification requirements for written explanations when criminal records lead to adverse actions, and record type limitations prohibiting consideration of arrests without convictions or sealed records.

California's Fair Chance Act, New York City's Fair Chance Act, and similar laws impose substantial compliance obligations. Employers operating in multiple states must understand the specific requirements in each jurisdiction where they hire.

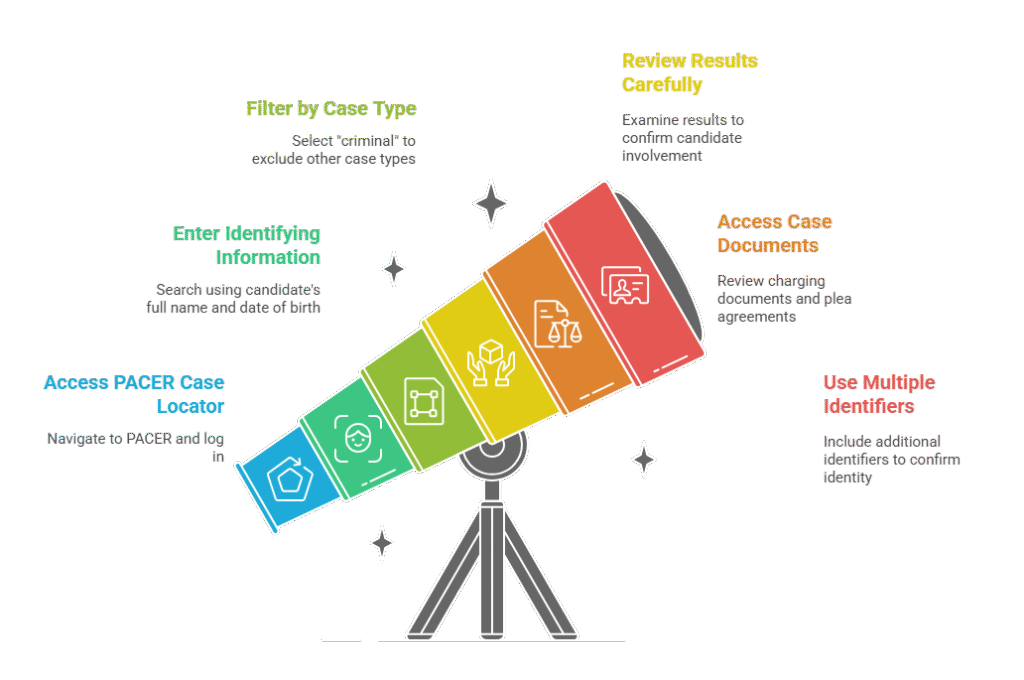

Documentation and Record-Keeping Best Practices

Maintaining thorough documentation of background check processes and adverse action decisions is essential for FCRA compliance and defending against discrimination claims. Employers should document each step of the screening process, from authorization to final hiring decisions.

Recommended documentation practices include:

- Retention of signed authorization forms: Maintain records showing proper consent was obtained, typically for at least three years

- Adverse action documentation: Keep copies of pre-adverse action notices, background check reports provided to candidates, and final adverse action notices with dates sent

- Individualized assessment records: Document how you evaluated the relationship between criminal convictions and job responsibilities

- Dispute resolution records: Maintain documentation of investigations and responses when candidates dispute findings

This documentation demonstrates FCRA compliance, defends against discrimination allegations, and provides evidence of consistent policy application.

Common Employer Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even well-intentioned employers frequently make errors when conducting federal and state criminal background checks that create compliance risks and screening gaps. Understanding these common mistakes helps organizations develop more effective background check policies and avoid costly litigation or negligent hiring liability.

The most prevalent mistake is assuming that ordering a "criminal background check" automatically searches both federal and state court systems comprehensively. Basic background check packages typically include only county-level searches in the candidate's current location or a national database search that could miss significant criminal history. Another widespread error is searching only the candidate's current county rather than all locations where they've lived.

Overlooking Federal Court Searches

Many employers never search federal court records because they don't understand which types of offenses are prosecuted federally or don't realize federal searches require separate procedures. This oversight is particularly problematic for positions in finance, healthcare, and other regulated industries where federal crimes like securities fraud, healthcare billing fraud, or controlled substance violations are highly relevant.

Federal court searches are especially important for executive and financial management positions where federal white-collar crime prosecutions reveal patterns of financial misconduct, healthcare practitioners to identify charges for prescription fraud or HIPAA violations, and positions requiring security clearances. Employers should specifically request federal district court searches from their screening vendors. The relatively low incremental cost of federal searches (typically $15-40) is modest compared to the risk exposure from missing serious federal criminal history.

Inconsistent Application of Background Check Policies

Applying different background check protocols to similarly situated candidates creates discrimination liability under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. If an employer conducts comprehensive federal and state searches for some candidates but only basic county searches for others in the same position category, disparate treatment claims may arise.

Consistency requirements include standardized search scope for all candidates in the same position classification, uniform timing for conducting background checks at the same point in the hiring process, equal consideration standards applying the same criteria for evaluating criminal history regardless of demographics, and documentation of exceptions with legitimate, non-discriminatory business justifications. The EEOC's guidance emphasizes that policies must be applied consistently and individualized assessments should follow structured criteria.

Ignoring Record Verification and Accuracy Issues

Criminal background check reports sometimes contain errors including records belonging to different individuals with similar names, outdated disposition information, or cases that should have been sealed or expunged. Failing to verify questionable findings or provide candidates opportunity to correct inaccurate information violates FCRA requirements.

Background check accuracy issues often involve:

- Name matching errors: Common names generate false positive matches including someone else's criminal record

- Incomplete disposition information: Databases show arrest records without reflecting subsequent dismissals or acquittals

- Outdated records: Sealed or expunged convictions that should not be reported still appear in some databases

- Data entry mistakes: Court clerks occasionally transpose identifying information or case details

Employers should establish procedures for investigating and verifying any criminal records that would lead to adverse action, including confirming the record belongs to the candidate by checking multiple identifiers.

How to Design Position-Specific Screening Protocols

Creating position-specific screening protocols allows employers to match background check depth with actual position risks and requirements. This targeted approach ensures thorough screening for high-risk positions while controlling costs for lower-risk roles. The first step involves conducting a thorough job risk assessment to determine which types of criminal history are most relevant to each position category.

Once risk levels are established, employers can create tiered screening levels:

- Tier 1 (High-Risk Positions): Comprehensive county searches in all residence locations for seven years, federal district court searches, state repository checks, and employment and education verification for positions with financial responsibilities, vulnerable population access, or security clearance requirements

- Tier 2 (Moderate-Risk Positions): County searches in primary residence locations for seven years, national database searches with county verification of findings, and employment verification for positions with moderate liability exposure

- Tier 3 (Lower-Risk Positions): County search in current location, national database search for identification of potential records, and basic identity verification for entry-level positions without sensitive access

- Industry-Specific Additions: Supplemental searches based on regulatory requirements, such as federal court searches for financial services or professional licensing board checks for healthcare

This tiered approach ensures resources are allocated where they provide the greatest risk mitigation value.

Financial Services and Fiduciary Positions

Positions involving financial management, access to company funds, or fiduciary responsibilities require particularly thorough background screening. These roles create significant opportunities for fraud, embezzlement, and financial misconduct, making federal court searches essential for identifying white-collar crime convictions.

For financial services positions, employers should implement comprehensive protocols including federal district court searches across all relevant jurisdictions to identify securities fraud, wire fraud, tax evasion, and money laundering. County-level criminal searches in all residence locations for at least seven years reveal theft, fraud, forgery, and identity theft. Credit report checks (with proper FCRA authorization) show patterns of financial irresponsibility, and professional license verification confirms credentials and reveals disciplinary actions.

Financial institutions regulated by FINRA, FDIC, or state banking authorities often face specific background check requirements mandating federal court searches and extended lookback periods.

Healthcare and Vulnerable Population Access

Healthcare positions and roles involving access to children, elderly individuals, or disabled persons require specialized screening protocols focusing on violent crimes, sexual offenses, abuse, and drug-related convictions. Both federal and state searches are important because drug trafficking may be prosecuted federally while assault and abuse typically appear in state courts.

Healthcare position screening should include:

- County criminal searches: Identify assault, battery, sexual offenses, domestic violence, abuse or neglect, and drug crimes

- Federal court searches: Reveal controlled substance violations, healthcare fraud, HIPAA violations, and prescription fraud

- State professional licensing board checks: Confirm licenses and identify disciplinary actions or restrictions

- Registry checks: Include sex offender registries and abuse/neglect registries where applicable by state law

Many states require healthcare employers to conduct fingerprint-based background checks through state repositories for licensed practitioners, direct care staff, and anyone with patient access.

Understanding Lookback Periods and Reporting Limitations

Lookback periods define how far back in time a background check searches for criminal records. These periods are governed by FCRA, state laws, and employer policies. Understanding applicable lookback periods is essential for compliance and setting candidate expectations.

The FCRA establishes federal baseline standards for reporting criminal convictions and other adverse information. Under federal law, criminal convictions can be reported indefinitely with no time limit, but arrests without conviction can only be reported for seven years from the arrest date. These federal standards apply nationwide unless state law is more restrictive.

Many states have enacted laws imposing stricter limitations than federal FCRA requirements. For example, California law prohibits reporting criminal convictions older than seven years for positions paying less than $75,000 annually. New York law prohibits reporting convictions where the criminal record has been sealed or expunged. Massachusetts limits reporting to seven years for any criminal records except certain serious felonies. Employers must apply the most restrictive applicable law for each candidate based on work location.

Exemptions and Exceptions to Standard Lookback Periods

Lookback period limitations typically include exemptions for certain high-salary positions or positions with specific responsibilities. Common exemptions to seven-year lookback limitations include positions with salaries of $75,000 or more annually, positions with access to $1 million or more in assets, law enforcement and criminal justice positions, and positions requiring state or federal security clearances.

Even when exemptions apply, employers should consider whether very old convictions remain relevant to current employment decisions. A 15-year-old conviction may have limited predictive value for current conduct, especially if the candidate has demonstrated rehabilitation. Some jurisdictions provide no exemptions and apply strict seven-year limitations regardless of salary or position type.

Handling Sealed, Expunged, and Pardoned Records

Sealed, expunged, and pardoned criminal records require special handling under both FCRA and state laws. These records have undergone legal processes to limit or eliminate their visibility and use in employment decisions. Employers who improperly consider these records face significant legal liability.

Sealed records are court records made confidential and not accessible to the public or most employers. These should not appear in standard background check reports, and if they do, employers generally cannot consider them. Expunged records are convictions that have been erased or removed from a criminal recordâlegally, it's as if the conviction never occurred. Pardoned records are convictions where the governor or president has granted clemency, which may restore civil rights but don't always erase the conviction from the criminal record.

The treatment of these record types varies by state. Generally, the safest approach is to disregard any sealed or expunged records and not consider them in employment decisions.

Balancing Screening Thoroughness with Hiring Efficiency

Employers face ongoing tension between conducting thorough background checks and maintaining efficient hiring processes. Comprehensive federal and state searches across multiple jurisdictions take time and money, but inadequate screening creates negligent hiring risks. Finding the right balance requires strategic planning, clear policies, and realistic timeline expectations.

The key to balancing thoroughness with efficiency is starting background checks at the appropriate point in the hiring process. Best practice involves starting background checks after initial interviews when the candidate pool has been narrowed or after extending conditional offers of employment. This allows screening to proceed while final interviews or negotiations continue.

Employers should communicate clear timelines to candidates about background check processes. Transparency about typical turnaround times sets appropriate expectations and reduces candidate anxiety. This communication demonstrates professionalism while giving candidates the opportunity to disclose relevant information proactively.

Conditional Offers and Background Check Timing

Conditional offers of employment have become standard practice for managing background check timing while complying with ban-the-box laws. A conditional offer means the employment offer is contingent upon successful completion of background screening and other pre-employment requirements.

The conditional offer approach complies with ban-the-box laws requiring delays in criminal history inquiries, allows employers to assess candidate qualifications before investing in comprehensive background checks, provides legal protection if adverse action becomes necessary, and demonstrates good faith in the hiring process. When extending conditional offers, employers should clearly state all contingencies in writing, including successful completion of background checks, verification of credentials and licenses, and satisfactory reference checks.

Managing Volume Hiring and Seasonal Screening Needs

Organizations conducting high-volume hiring or with seasonal staffing needs face unique background screening challenges. Processing hundreds of background checks simultaneously requires efficient systems and potentially expedited services, but efficiency cannot compromise thoroughness or compliance.

For volume hiring situations, employers should establish relationships with background screening vendors who can handle volume surges, negotiate volume pricing to control costs during peak periods, implement tiered screening protocols so not every position requires the most comprehensive package, use technology platforms that integrate background screening with applicant tracking systems, and plan hiring timelines that account for background check turnaround times to avoid last-minute rushes.

Conclusion

The distinction between federal and state criminal background checks is fundamental to comprehensive pre-employment screening. Federal and state court systems operate independently, maintain separate records, and require different search methodologies. Employers must deliberately design screening protocols that include both federal court searches through PACER and state-level county searches across relevant jurisdictions. By implementing risk-based screening strategies, maintaining FCRA compliance, understanding jurisdiction-specific requirements, and partnering with quality background screening vendors, employers can conduct thorough due diligence while maintaining efficient hiring processes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does a criminal background check include federal and state records?

Standard criminal background checks do not automatically include both federal and state records unless specifically requested. Most basic packages include only county-level state court searches. Federal court searches require separate searches through PACER or specialized screening services.

How can I search federal court records for employment screening purposes?

Federal court records are accessed through PACER at pacer.uscourts.gov by creating a free account. You can search individual districts or use the nationwide Case Locator. Alternatively, employers can work with background screening companies that include federal court searches in their services.

What types of crimes appear in federal court versus state court?

Federal courts prosecute violations of federal statutes including drug trafficking, immigration offenses, white-collar crimes, federal weapons violations, and terrorism-related charges. State courts handle approximately 90% of criminal prosecutions including most violent crimes, property crimes, DUI offenses, and violations of state criminal statutes.

How long does it take to complete federal and state background checks?

Federal court searches through PACER typically take 1-3 business days. State-level county criminal searches range from 1-2 days for online systems to 3-7 days for manual research. Comprehensive background checks searching multiple counties and federal courts usually take 3-7 business days total.

Are arrest records without convictions included in federal and state background checks?

Practices vary by jurisdiction and screening methodology. FCRA allows reporting arrests for seven years. However, many employers and screening companies have policies against reporting arrests without dispositions. EEOC guidance discourages considering arrests without convictions as potentially discriminatory.

Can I conduct my own PACER searches instead of using a background check company?

Employers can legally conduct their own federal court searches through PACER. However, they must still comply with FCRA requirements including obtaining written authorization and following adverse action procedures. Many employers find that professional screening services provide better efficiency and compliance support despite additional costs.

Additional Resources

- Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) Overview and Compliance Guide

https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/using-consumer-reports-what-employers-need-know - PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) System

https://pacer.uscourts.gov - EEOC Guidance on Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records

https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/arrest-conviction-records - Professional Background Screening Association (PBSA)

https://www.pbsa.org - National Association of Professional Background Screeners Resources

https://www.napbs.com/resources - Understanding the Federal Court System - U.S. Courts Guide

https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure

GCheck Editorial Team

Meet the GCheck Editorial Team, your trusted source for insightful and up-to-date information in the world of employment background checks. Committed to delivering the latest trends, best practices, and industry insights, our team is dedicated to keeping you informed.

With a passion for ensuring accuracy, compliance, and efficiency in background screening, we are your go-to experts in the field. Stay tuned for our comprehensive articles, guides, and analysis, designed to empower businesses and individuals with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions.

At GCheck, we're here to guide you through the complexities of background checks, every step of the way.